The Stories Behind the Seams of a Pennsylvania Tailcoat,

ca. 1795-1810

In 2021, the Berks County Historical Society (BCHS) transferred to the Fashion Archives and Museum of Shippensburg University (FA&MSU) a child’s indigo jacket with no known provenance. Despite the loss of the coat’s original history, this jacket most likely had Berks County origins and probably did not travel far outside the county before its initial transfer and preservation at Berks County Historical Society. Assuming that was the case, this coat raises fascinating questions about politics, domestic management, immigration, and—sadly—the forced labor of the enslaved that permeated Federal American society as a whole and pertained to more states than Pennsylvania alone. At the same time, this coat invites analysis of fabric production and fashion consumption in a localized yet multi-cultural area. This jacket is currently mounted on a temporary exhibition mannequin where the directed lighting emphasizes the details: its primary material, worn sleeves, buttons, tails, neckline, size, and most importantly, its deep indigo color.

Indigo Jacket (Front) from the Fashion Archives & Museum of Shippensburg University. Photo courtesy of Hayley Anderson.

Indigo Jacket (Back) from the Fashion Archives & Museum of Shippensburg University. Photo courtesy of Hayley Anderson.

When looking at the fabric, a viewer might conclude that the dyed material resembles cotton’s soft and light texture and overall appearance. However, compared to something made from pure cotton, the coat’s fibers are slightly irregular, a characteristic of linen since it was handspun, and more importantly, of its bamboo-like structure that features cross-hatching and nodes. Long used for underwear, household textiles, and light garments, linen is a breathable and robust fabric that becomes softer and more comfortable with every wash. The elbow portions of this coat are worn from use by a small and active child, demonstrating that the linen was unable consistently to maintain the deep blue color under the stress of regular use. Difficulty in successfully absorbing dyes permanently is another key characteristic of linen. The wearer wore this jacket fairly frequently before outgrowing it and was active while wearing it. The linen material held up extremely well despite the coat’s period of use, followed by approximately 200 years of storage.

Looking at the front of the coat, one can see four fabric-covered buttons used to fasten the two front pieces. The scraps of fabric cover the button mold, which is hard and could possibly be wood. But it is difficult to know for certain without doing damage in the process. Choosing these buttons over something more striking, such as metal or ornamental buttons, due to the date range, can signify that this coat was not something of a showpiece but something someone could wear to run around in or get dirty without any serious repercussions. The neckline is V-shaped and is deep enough to expose the neck and the child’s shirt. At the back, two separate tails pleated for added fullness hang below the center back waistline, giving the coat a bit of flair when worn. The coat’s size reveals something more substantial: due to its small proportions, it is obvious that it belonged to a child. Judging by the proportions, the size and age of the original wearer must be somewhere of a small child, perhaps three to four years old at the most. Most importantly, the coat’s color, indigo, indicates that the linen was dyed to cover its natural color, which ranges from cream to tan. However, since chemists did not produce indigo chemically until the mid-19th century, the dyeing process between 1795 and 1810 was all-natural.

Children’s fashion first emerged in the 1770s as something separate and different from adult styles. For the first time, garments were designed to have a looser fit and more freedom of movement, which improved a child’s comfort level and permitted more physical activity. The new garment for boys was called a “skeleton suit,” consisting of ankle-length trousers that buttoned into place over a jacket. The suits were ideal for play and for dressier occasions. Thus, the skeleton suit has become the icon of the momentous transition from viewing and dressing children like small adults to the new revolutionary concept of childhood as a special period of human life.

Skeleton suits were distinct from adult men’s clothing, which consisted of breeches and, in the 1790s, highly tailored double-breasted tailcoats with exaggerated wide lapels and collars cut to sit high on the back of the neck. Children like bright and vibrant colors, and blue was one of many possibilities. The construction of the indigo jacket matches that of adult male fashions and is distinct from the jackets of the skeleton suit, which had buttons at key points around the waistline for fastening the trousers around the boy’s body for a neat appearance.

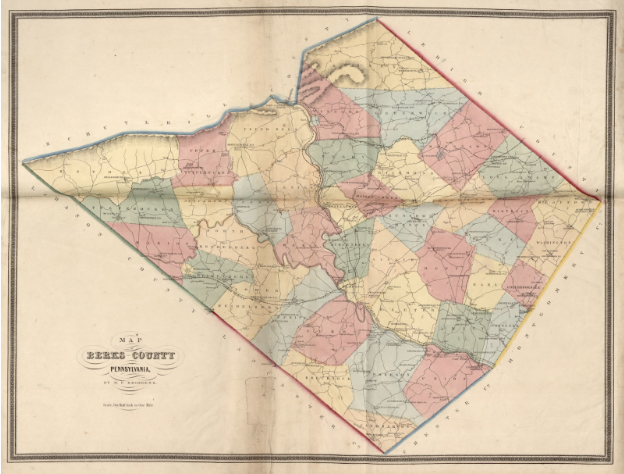

An 1862 Township Map of Berks County, Pennsylvania, from Actual Surveys by L. Flagan. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Considering the coat’s probable origins in Berks County, located in the south-central region of Pennsylvania, the county was once and continues to be known for its fertile land that allowed the county to be very prosperous in terms of agriculture. Before 1720, a few immigrants, and those already present in the county, worked the fields and began to construct the foundations of a county that would soon be home to roughly 420,000 people over the course of three centuries. Once immigration became profitable in the 1700s, businesses shipped thousands of immigrants to Pennsylvania to escape the problems of the Old World, creating a county of hard-working immigrants. Of these immigrants who traveled “across the Pond,” the largest group of non-English immigrants were from the many German-speaking areas along the Rhine River. These immigrants naturally brought aspects of their societies and cultures with them, establishing and expanding Germanic communities throughout Berks County. As a result, Berks County was enriched with a Pennsylvania Dutch ethnic culture and a German identity, unlike its counterparts in Europe by the end of the colonial period.

Of course, other immigrants came to Pennsylvania from abroad during and after the 1720s. For example, in Berks County, there were Scots-Irish, Welsh, French Huguenots, Jews from the Spanish Empire, German and Irish Catholics, and others present around the same time when the county was establishing itself as having a rich Germanic heritage.

Due to the complexity of the various groups of immigrants entering Berks County before the American Revolution and during the periods afterward, it is almost impossible to pinpoint where the coat originated. The coat has a statistical likelihood of being connected to the German-speaking people due to the large population living in Berks County between 1720 to 1810. However, it is equally likely that the coat could have belonged to one of the other smaller groups of immigrants entering the county. With the complete lack of provenance, only the population statistics can permit the tentative conclusion that coat was associated with Berks County Germans.

Stemming from the era of the Homespun movement starting in 1767, politics encouraged Americans to start manufacturing and producing their goods instead of relying on England, which had a stranglehold on the American economy. Due to this movement, many Americans made their clothing through traditional processes throughout the colonies, allowing others to take the approach to create a surplus of goods to sell to the general public. From 1795 to 1810, the possibility exists that the coat’s construction could have ties to a slop shop somewhere along the east coast instead of being tailored specifically for the individual. However, slop shops catered largely to the lower levels of society, targeting adult males in general and sailors in particular because they needed to acquire clothing quickly during short stays on land. Throughout the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth century, some Americans purchased different ready-made garments from these inexpensive slop shops and then altered them to improve the fit. Therefore, the coat is more likely to have been tailored and made at home rather than produced in one of these slop shops for several reasons:

Reason 1: Slop shops were mainly for those who worked in or around shipyards on the eastern coast. Because the intended audience for these types of garments were the adult working classes, most of the clothing was loose-fitting to allow workers to move around efficiently. The coat’s structure with its snug sleeves and tails does not resemble the style preferred by the laborers around these areas. Additionally, the jacket is too small for anyone of working age.

Reason 2: Except for shoes, simple outwear, and unfitted garments, ready-made clothing was inferior to tailored clothing due to fashion standards during the period. When it came to clothing, those who preferred to wear ready-made clothing were considered subordinate to those who opted to get their clothing tailored. After 1787, American enslavers were major consumers of ready-made garments for their enslaved, for those enslaved were not legally permitted to wear clothing similar to that of free citizens.

The coat was most likely tailored for its intended wearer since the dimensions were very particular and anchored in contemporary fashion, not practical work attire. There are no signs on the fabric that the fit or size were ever altered or adjusted in any way; alterations leave marks on a garment. Furthermore, due to the economic prosperity as a result of agricultural production in this region of Berks County, one could assume that the family had enough resources to purchase a tailored piece of clothing for a child or potentially having the sources to make the piece of clothing at home. Of course, we should not neglect the possibility that the family could have purchased or commissioned the jacket from another source. Moreover, another possibility is that the coat was specifically tailored from the scraps of a much larger project and represents an economical use of fabric after the construction of a garment intended for an adult or a larger child. Irregular stitches and short-cuts to deal with the raw edges of the fabric indicate that the coat was made by a competent needleworker, but not one with a professionally trained hand.

Someone needed to purchase or create the fabric beforehand to construct the coat. The linen could be from a store, but the possibility that it was made at home is equally strong. If purchased from the store, the linen could have been local or produced somewhere outside of Berks County due to the period of the coat’s construction (1795 to 1810). It would have been much easier for most people to purchase a linen piece consisting of a few yards than to produce the yardage needed to construct the coat. It would save time to purchase or barter for ready-made goods and certainly foreshadows the consumerism that would eventually take the colonies by storm. Since fabric was sold by the finished piece of varying lengths, and customers purchased the entire piece, it is entirely possible that the coat was indeed constructed from remnants left after a larger garment was created.

Nevertheless, before 1774, households preferred to use locally produced linen cloth because it was more readily available and cheaper than those outside the county. Eventually, the imported varieties of different fabrics became increasingly available and were used with and against local products. Consequently, consumers were able to pick and choose from various styles of fabrics. Because of such competition, stores advertised stamped and printed goods limited throughout the mid-to-late 1700s.

In order to use the linen to make the coat, it had to be woven from yarn made of flax plant fibers, particularly the flax plant from the family Linaceae: Linum usitatissimum. This plant has two varieties of flowers, blue and white, and has grayish-green stems. The height of the plant is generally around three to four feet tall, with the fibers used to make the yarn toward the top of the stem. To grow the flax plant, the plant needed a temperate and relatively equitable climate that lacked copious amounts of rain. Because of the climate and the environment of Berks County, there is a possibility that the flax plant was a plant locally grown in the area.

The Production of Linen:

Spinning wheel made by Jacob Klein, active in eastern PA in the 1840s. Photo courtesy of Abigail Koontz.

After spinning the fibers into thread, one can use it to weave linen to construct garments or household textiles. From start to finish, this process could take an entire year or more from seed to cloth, especially when environmental factors come into play. The time factor certainly permits the supposition that there could be a good chance that the linen came from the store after being produced in someone else’s home. Of course, this is all speculation because hand spinning and weaving were a routine part of thrift and home production through the 1830s.

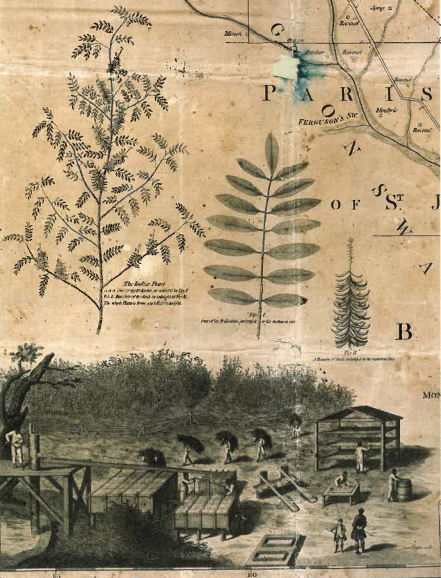

The production of indigo to make the dye used to color the fabric used in this coat is essential since its production was not possible in the northern portion of the country. Due to the lack of a proper climate, slave labor in the sub-tropical areas of the Carolinas was most likely the culprit in obtaining the processed indigo dye. Unfortunately, this meant the coat was partially a product of enslaved labor, much like many essential products bought and created in the colonies and afterward.

Courtesy of the Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library of Duke University used in the magazine Early American Life.

Grown in the sub-tropics, the indigo plant was generally a five-foot plant from the Legume family: Indigofera tinctoria. To get the most out of the plant, it was essential to immediately collect the plant and remove its buds and leaves after harvesting. In 1826, York resident P. Imswiler published The Family Dyer and provided several recipes for working with indigo at home. Although the English recipes have been included here, the book was in fact bilingual, with all the explanatory materials and information appearing in English and German. The existence of such a book hints at the possibility that the coat was a product of home manufacture.

Excerpts from The Family Dyer

The existence of this small coat generates several theories for interpretation:

Theory 1: Using the indigo plant to make the blue dye used in the coat, the blue color thus represents loyalty in the newly founded country of America. Furthermore, the United States federal government alludes to the color blue in the American flag as a symbol of justice, vigilance, and perseverance. Combining these thoughts, this color recalls a story of moving forward despite the difficulty observed and overcame during the years leading up to the country’s foundation and for the years it endured afterward. For instance, between 1795 and 1810, America was slowly establishing itself as a nation. America began to repair itself after the upheaval of the Revolution (1775 to 1783) and through the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1788. Because of these events and those soon to follow, Americans continued to push through these challenges to establish the country now known today as the United States of America.

Theory 2: The coat was clearly a product of the “Made in America” patriotism that originated with the Homespun Movement starting in 1767. By resisting outside manufacturing in Europe, Americans began to find their own identity and economic path despite outside influences, especially in fashion. Viewed through this lens, the coat could be a product of this resistance to dependence upon imported goods.

Theory 3: The coat potentially aligned the son’s appearance with a fashionable father figure within the household. Most children try to resemble or emulate their parents in one way or another, and through fashion, the coat gives the little boy a chance to become one step closer to emulating his parent. In some cases, the scraps of clothing made for other family members were used to create a similar garment for more minor children. This technique is particularly the case for women who used scraps from their dresses to make smaller versions for their children, which could be the case in our coat’s regard. The adoption of a grown-up style implies that the boy was already being taught to behave more like an adult.

From the finished product to its raw materials, the little indigo jacket bears a story of hard labor and a little boy who most likely lived within a farming community in or around Berks County. Of course, not every question has an answer, but the ability to use clues and knowledge of materials brings to life a many-layered interpretation of the coat that includes politics, domestic management, immigration, and—sadly—the forced labor of the enslaved.

Cannon, Alexandria. “Gradual Abolition Act of 1780.” Digital Encyclopedia of George Washington. Accessed April 25, 2022. https://bit.ly/3fEr48p

Hersh, Tandy. Cloth and Costume, 1750-1800, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania. Camp Hill, PA: Cumberland County Historical Society, 1995.

Imswiler, P. The Family Dyer. York, PA: 1826.

Miller, Randall, and William Pencak. Pennsylvania: A History of the Commonwealth. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 2009.

Możdżyńska-Nawotka, Małgorzata. “Dressed ‘as If for a Carnival’: Solving the Mystery of the Origins of Children’s Fashion. A New Perspective on the History and Historiography of Children’s Dress.” Textile History 51, no.1 (2020): 5–28. doi:10.1080/00404969.2020.1743930

Putman, Tyler R. “Joseph Long’s Slops: Ready-Made Clothing in Early America.” Winterthur Portfolio 49, no. 2/3 (2015): 63–91. https://doi.org/10.1086/683042.

Rupp, Rebecca. “Indigo: The Devil’s Dye.” Early American Life (August 2010): 42-49.

Storey, Joyce. The Thames and Hudson Manual of Dyes and Fabrics. London: Thames and Hudson, 1992.

USAGov. “The American Flag and Its Flying Rules.” USA. Last modified May 14, 2021. https://bit.ly/3C8Cw3X

Christopher Ott, Applied History Graduate Student at Shippensburg University, Spring 2022