Explore how American fashion changed in response to events surrounding the American Revolution

History of Homespun 1760s-1770s:

Important Dates:

Watch the video below to get a brief overview of the homespun movement and see some more examples of homespun fashion:

With the end of the Seven Years War in 1763, England began the process of paying back its war debts. Secretary of the Exchequer, modernly titled Prime Minister, George Grenville argued that taxes should be levied in the colonies to help pay for colonial defense against the French. In response, colonists in various locations met and signed non-importation agreements in the hopes that boycotting the newly taxed products would place pressure on British merchants, who would then pressure Parliament to alter its policies.

Example of a dress made from luxurious silk damask in the 1750s, then altered during the 1770s. It belonged to a wealthy woman in upstate New York.

Fashion Archives & Museum Collection

Cloth, like tea, also became politicized through the nonimportation agreements. Revolutionaries especially targeted silk and lace as symbols of luxury and status, specifically in the context of British imperial oppression and English extravagance. John Adams, in a letter to James Warren, wrote that “Silks and Velvets and Lace must be dispensed with [as] Trifles in a Contest for Liberty.” The Continental Association of 1774 declared that wool was the best republican material, because it was the furthest thing from the British extravagance of silk and lace. With the nonimportation agreements limiting the supply of cloth coming into the colonies, combined with the dislike of luxurious cloth, the colonists had to create their own cloth for practical and political reasons. One of the ways that women created their own cloth was through spinning bees. From March 1768 through October 1770 New England newspapers recorded over sixty instances of spinning bees where women gathered to spin yarn and cloth. Spinning was one way that America could begin to manufacture for itself, or at least provision the colonists until Britain repealed the odious Townshend Acts. Spinning was a strictly female task, but because it held such political significance, it received a lot of attention, with one newspaper claiming that these women “determined the Condition of Men, by means of their Spinning Wheels: And Virgil intimates, that the Golden Age advanced slower, or faster, as they spun.”

18th-century spinning wheel

Spinning bees could take a variety of forms. Women sometimes held spinning matches where a small number of women competed to see who could spin the greatest amount of yarn. During these spinning demonstrations, women occupied a public space, such as the town square, and spun, often attracting large numbers of spectators. Even Abigail Adams supported the homespun movement, writing to her husband stating “As for me I will seek wool and flax and work willingly with my Hands, and indeed [there] is occasion for all our industry and economy.” Homespun, which in the eighteenth century meant “made in the USA” but not necessarily made entirely by hand, became important during the revolution because it was the opposite of extravagant British fashion. Even after the revolution, homespun was a way to show republican simplicity, which might be why George Washington chose to wear a homespun suit for his first inauguration. The wool for his suit came from a mill in Connecticut.

George Washington wore a homespun outfit for his first inauguration [photo credit: Mount Vernon]

1780s US History and Silk Trade:

Important Dates:

Map of the United States according to the Treaty of Paris of 1783 (Photo Credit: New York Public Library Public Archive)

The United States won independence in 1783 and formalized relations with the British by signing the Treaty of Paris of 1783 (not to be confused with the Treaty of Paris of 1763). However, the treaty left many issues unresolved, and the British blocked the newly formed U.S. from its principle trading partners: British possessions in the Caribbean and the British Isles. The French began working towards increasing trade and military relations with the U.S. during this time. France was especially interested in American military assistance for the defense of French Caribbean colonies, such as Saint Domingue (modern day Haiti). The early relationship between France and America was based on a treaty signed during the Revolutionary War in 1778. The treaty recognized the U.S. as an independent country and guaranteed French military assistance to help fight the British. This also helped open trade relations with the U.S. after the war.

Fashion plates, such as these, were used to show potential American customers different clothes that were currently fashionable in France. To learn more about fashion plates visit the National Portrait Gallery’s website (Photo Credit: National Portrait Gallery UK)

With trade restrictions in place several materials, such as silk, were difficult to obtain. English and Chinese silk could only be acquired directly from the English and was available only to the wealthiest of colonists such as tobacco plantation owners and shipping magnates. These wealthy colonists often traded with each other and used agents to buy materials and finished clothing from England. For example, tobacco planters used English agents who sold their tobacco (or other raw resources) and held the money from those sales to make purchases of finished goods such as silk clothing. As a result, the colonists could not “shop” in advance for these products and they would not know exactly what they got until the agent shipped the product back to them in the colonies. Details provided to the agents were vague and limited to qualities such as the size and cuts of the clothing and basic instructions such as it having to be “fashionable.” Some Americans, such as merchants, were more detailed in their requests to English dressmakers and tailors. At times they made the trip to England where they were better able to describe, see, and select the designs they desired; they also brought back yardage to be used in the colonies to produce garments. However, colonists who made use of these local merchant shops had limited choices as they had to rely on what the merchants were able to acquire. With the trade restrictions imposed by the British after America gained independence, British clothing became hard to get and more and more Americans began buying from the French.

The blue ribbed silk coat, ca. 1780s, on the right is in the English style (Fashion Archives and Museum Collection). Similar to the simplistic design of George Washington’s Inaugural coat (pictured above) which was also used in the US. Compared to the three piece suit gold suit one the right which was of French origin purchased by US General Jonathon Williams on a trip to Europe. The French style tended to be more elaborate with the goal of displaying one’s on social status, in this case upper class. Whereas suits like that of the blue ribbed coat or George Washington’s coats were meant to be simple displaying the republican ideas of equality. (Three piece gold suit Photo Credit: Philadelphia Museum of Art)

The blue ribbed silk coat, ca. 1780s, on the right is in the English style (Fashion Archives and Museum Collection). Similar to the simplistic design of George Washington’s Inaugural coat (pictured above) which was also used in the US. Compared to the three piece suit gold suit one the right which was of French origin purchased by US General Jonathon Williams on a trip to Europe. The French style tended to be more elaborate with the goal of displaying one’s on social status, in this case upper class. Whereas suits like that of the blue ribbed coat or George Washington’s coats were meant to be simple displaying the republican ideas of equality. (Three piece gold suit Photo Credit: Philadelphia Museum of Art)

Since the 1770s, French immigrants had been arriving in the US, especially the city of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. They brought with them their culture. During this time period, French culture was considered the most advanced and sophisticated and thus people were open to adopting French styles. Philadelphia was the U.S. capital at the time and became a host to a large population of French immigrants. This population increased dramatically during the French Revolution which began in 1789. French immigrants brought with them their own ideas on fashion. Initially some French immigrants imported the concept of dressing differently based on social status (rich vs. poor). However, other French immigrants brought over concepts from Revolutionary France that challenged the idea of dressing differently based on class. During this time there was a push by different groups (such as the Quakers) in the U.S. who promoted republican ideals of equality and that fashion should be equal no matter if someone is rich or poor. However, not everyone followed this trend and others still found ways to show off their status. George Washington managed to find a balance between republicanism and the flashier French trends in his wardrobe. For example, he often wore a simple coat in dull or muted colors. However, the coat was form fitting and professionally tailored, which signified that he was not a field laborer and thus didn’t need loose-fitting clothing. That in itself became a status symbol. Trade relations between the British and the US did not normalize until 1794 with the signing of the Jay Treaty.

1790s History:

Important Dates:

The Muslin Dress: Muslin fabric is fine, smooth in texture, and woven from evenly spun warps and wefts or fillings. The muslin outfit is given a soft finish (bleached or dyed) and is sometimes patterned in the loom or hand embroidered like the one below. The muslin gown originated in India and became popular in the West Indies, where ladies on plantations needed to keep cool in the tropical climate. Upon its introduction to Europe and later in the United States, it was embraced by the fashionable ladies who preferred the simpler neoclassical aesthetic that began to dominate tastes. Marie Antoinette was depicted wearing a chemise gown made of layers of imported muslin in a royal portrait by Elisabeth Vigee-Lebrun. The portrait led to a scandal which was exacerbated by the fact that the gown was not made of French silk. Muslin outfits were designed for the hot summer weather but could still be worn in the winter. Despite the scandal, it became a staple of the fashionable wardrobe and led directly to the simple white gowns that became fashionable in the 1790s and early 1800s.

Child’s Muslin Dress, ca. 1805, covered with candlewick hand embroidery.

Fashion Archives & Museum Collection

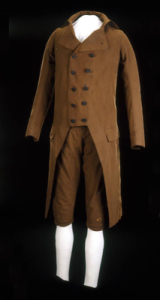

Dressed “as if for a Carnival”: Beginning in the 1770s, children’s garments were designed to have a looser fit that would allow more freedom of movement which improved a child’s physical comfort level. During this time there was a transition from viewing and dressing children like small adults to the new concept of childhood being a special period in life with its specific needs, which included clothing. However, as children grew, they dressed similarly to their parents as part of becoming more mature. This dark blue linen tailcoat was made of homespun and was essentially a comfortable miniature version of a man’s tailcoat, so a boy could look just like his father.

Homespun Boy’s Jacket, ca. 1795-1810, from Berks County, Pennsylvania

Fashion Archives & Museum Collection

Teacher Resources

Lesson plan

The Revolution of Fashion: The Different Styles

The Revolution of Fashion: Design Your own Fashion Plate

The Revolution of Fashion: Guided Reading Questions

Fashion Plate Templates