The story behind a surviving parachute blouse (c. 1944).

In 1944, Gertrude Gaskin Fagan (1918-2020), nicknamed “Billie,” received a gift from Italy: a blouse made out of “parachute silk” from her brother, Jack Drum (1918-2011). The unknown Italian tailor who drafted the design, adding lace trimmings and faux pockets, also created an elegant and useful garment. However, the symbolic significance of the blouse carried even greater weight.

-These pictures are courtesy of the Fashion Archives and Museum of Shippensburg University.-

Billie Gaskin’s blouse is one of many surviving examples of parachute clothing and other souvenirs brought home by American soldiers. The parachutes repurposed into these clothing pieces usually represented the soldiers’ experiences and triumphs, and to be honest, their “sticky fingers.” Instead of being officially turned in for repair and reuse, these parachutes received a new purpose as clothing items such as this blouse. The “liberated” parachute showed the practicality and resourcefulness of American soldiers who understood the severe shortages and rationing their loved ones endured on the home front. While most items brought home by American soldiers overseas were often seen as souvenirs, this blouse represented that deeper concern: family.

In Billie and Jack’s youth, their parents, Lillian (1895-1966) and Keith Drum (1895-1931), shared a rented double house with Lillian’s parents in Carbondale, Pennsylvania. At the height of prohibition, Keith brewed beer in their basement and was often short-tempered and violent toward the rest of the family. Like many Americans, the Drum Family was hit hard by the Great Depression, which was made worse because Lillian’s parents and Keith died within four years. Lillian did her best to keep the family together throughout these tragedies, though as jobs in the area continued to disappear, she sent her older children to stay with her sister in New York for a time. While Billie graduated at the top of her class, Jack struggled in school and left it entirely at age 16 to enroll in the WPA forestry program. Billie later moved to New Jersey to accept a clerk job, while Jack moved to Connecticut to become a car mechanic. Jack had always been enamored with flying. When the United States entered World War II, he joined the military, becoming a belly gunner on a B-24 Liberator Bomber and eventually a sergeant in the Army Air Forces.

-Family pictures courtesy of Judith Schwenk-

As the Drums were facing hardships at home, trouble was also brewing on the world stage. Following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 and the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, the United States lost its leading supplier of silk. Replacing American dependence on Japanese silk was essential. Chinese supply may have been possible, but Japanese aggression made this unlikely. At different moments in American history, domestically produced silk had been explored, though the labor cost to produce it and the skill required to produce quality fiber were both significant obstacles. Another alternative was rayon, created by Louis Chardonnet in 1891. Rayon proved to be highly flammable, and the fibers were weak compared to other variations of natural fibers, rendering rayon unsuitable for military use. Despite these disadvantages, rayon showed the potential in the developing field of synthetic fibers, and it proved useful in several nonmilitary applications. Eventually, in 1935, the DuPont company patented nylon as a synthetic fiber. Nylon was stronger than rayon, harder to scratch, and moisture resistant; it also resisted changes to its shape and had excellent flow properties. Nylon became the standard material for American parachutes, one of which was made into the blouse that Billie Fagan received from her brother.

As World War II began, many Americans were more concerned about the livelihoods of the civilians in the war-torn parts of Europe and Asia than actively participating in another global war. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, the mindset of much of the country changed. The following day, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called upon Congress to declare war on the Empire of Japan. After the attack, a desire to avenge the fallen at Pearl Harbor caused hundreds of thousands of American citizens to enlist, determined to prevent future attacks on American soil. Jack Drum enlisted and answered the call to defend the nation as part of the Army Air Forces.

“Remembering Pearl Harbor.” Courtesy of CBS News.

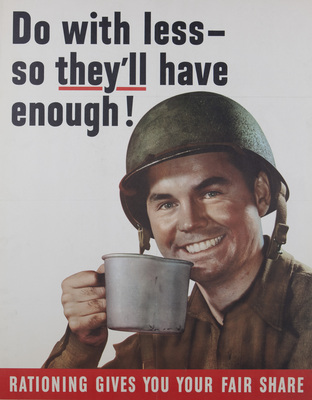

By December 11th, America’s war machine went into high gear throughout its widespread production and manufacturing outlets, turning America’s failing economy into one governed and determined by the war effort. Government officials raised taxes and issued bonds to support the war. Additionally, due to the war effort’s demand for goods and materials, many citizens at home were required to ration different necessities, including clothing. Because of this, many Americans went without certain goods readily available before the war to serve a common cause.

“Do with less – so they’ll have enough!” Courtesy of Office of War Information.

On July 10, 1943, the Allied armies began their Italian campaign by invading Sicily to rid the island of Italian and German forces. After little more than a month of fighting and the complete occupation of Sicily, the Allied forces began to plan a strategic amphibious assault on mainland Italy set for September 3, 1943. Their goal was to drive the Germans north, past the Italian borders.

-Family pictures courtesy of Judith Schwenk-

Sergeant Jack Drum of the United States Army Air Force filled his part during the campaign, flying over war-torn Italy and attacking German defenses with machine gun fire in the most dangerous position on the B-24 Liberator Bomber. While fighting to liberate Italy, Jack found himself with an American nylon parachute in 1944. Instead of obeying orders and turning it in, Jack headed to Abruzzi, Italy, to meet a tailor with the “liberated” parachute. The tailor then transformed the parachute into multiple blouses for his sisters back home, giving them a more practical gift than a simple souvenir of his time in the service.

Billie treasured her blouse and came to the Fashion Archives & Museum on her 92nd birthday to donate it to the permanent collection. It is the only parachute garment in the collection that is associated with daily wear and not a wedding, which was the more typical use of “liberated” parachutes during the war.

Abend, Hallett. “Japan Picks on Uncle Sam.” Saturday Evening Post. November 25, 1939.

Andrews, Peter J. “The Invention of Nylon.” In Science and Its Times: Understanding the Social Significance of Scientific Discovery, Vol. 6. Gale, 2000. https://bit.ly/3E7Q7ei.

Esposito, Frank. “Plastics News.” Crain Communications Inc., August 4, 2014, sec. Search for “superpolymer” led to nylon. https://bit.ly/3xZcS08.

Forty, Simon. Allied Armies in Sicily and Italy 1943–1945. Images of War. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military, 2019. https://bit.ly/3SpwZNi.

Hagley Museum and Archive, and Science Photo Library. Nylon Production, 1940s. n.d. https://bit.ly/3ftLgK9

Hunt, Robert. Parachute Factory WWII. n.d. https://bit.ly/3C4xpln

Mason, Meghann. “The impact of World War II on women’s fashion in the United States and Britain.” (2011). https://bit.ly/3rlUOcP

Moskowitz, Daniel B. “HEMMED IN: With Wartime Clothing Restrictions, Giving an Inch Could Go a Mile for the War Effort.” World War II, April 2018.

Office of War Information. Do With Less–So They’ll Have Enough! Rationing Gives You Your Fair Share. 1943. 71cm x 56cm. https://bit.ly/3RsjOtM

“Remembering Pearl Harbor.” Video. Remembering Pearl Harbor. CBS News, December 4, 2016. https://cbsn.ws/3LYLpBu

Tawatao, Maya. “Sewing Sacrifice: American Women’s Fashions and Clothing in World War II.” (2019): 1. https://bit.ly/3dWmiTt

TeachersCollegesj. “How Did Pearl Harbor Affect the United States?” TeachersCollegesj: Knowledge repository and useful advices, November 21, 2020. https://bit.ly/3CmCXck.

Wagner, Carolyn. “Material Memories: The Parachute Wedding Gowns of American Brides, 1945-1949.” Ph.D. diss., University of Cincinnati, 2015. https://bit.ly/3y9sbDE

“World’s Silk Situation Snarled as If Kitten Had Ball.” The Science News-Letter 38, no. 22 (1940): 340–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/3916691.

Jonathan Creager, Richard Jones, and Christopher Ott, Graduate Students of Dr. John Bloom’s HIS 501: Applied History Class, Fall 2022