A brief history of the development of pineapple fibers into Filipino clothing during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Yearbook photo of Mary E. Byers

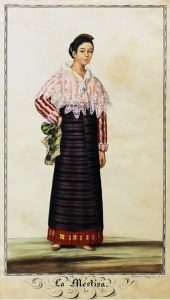

Mary “Betty” Byers graduated from Shippensburg University in 1927 and lived with her parents in Hagerstown, MD, while working as a public school teacher. In 1982, Mary Byers visited the university for the fifty-fifth anniversary of the class of 1927. She had been an exceptionally active student having joined ten organizations during her time at Shippensburg University. While visiting for the reunion, she found another way to become involved: she discovered the Fashion Archives. Between 1937 and 1939, Mary travelled in Pacific Asia and brought back shoes and dresses from many countries as souvenirs. Among the dresses was an embroidered piña cloth gown purchased in Manila, the capital of the Philippines. The dress was an excellent example of fashion of the 1930s. Influenced by the glamorous silhouette of the 1930s, it was a style known as a Traje de Mestiza, Spanish for Mestiza dress. It came in three parts: a camisa (the jacket/shirt), a long saya (skirt), and a pañuelo (kerchief).

The camisa is woven from a coarse but delicate beige netting that creates a close-fitting sheer bodice. For modesty, a silk slip would have been worn underneath the nearly transparent camisa. The camisa‘s oversized bell-shaped sleeves, known as “butterfly sleeves,” were inspired by the glamorous outfits in Hollywood feature films and entered into Filipina fashions in the 1930s. They are heavily embroidered in a floral pattern of yellow and red thread.

The piña cloth used to create the mestiza is finer and softer weaver than the jacket. The long, waist-high skirt is lightly embroidered with the same floral motif as the sleeves and along the edge of the train. The slim style of the skirt, with its dramatic flaring train, was known as the saya de cola which translates to a skirt with a tail.

The pañuelo is a square piece of coarse piña fabric folded diagonally into a triangle. The same yellow and red floral embroidery found on the sleeves is repeated in double stripes on the pañuelo’s back.

Pineapple cloth, commonly shortened to piña and or pina, is created from the fibers of pineapple leaves. Leaves are harvested from native pineapple plants from the western visayas and from the Spanish red pineapple introduced during the sixteenth century. Spanish red pineapple is frequently used due to the high yield of fibers obtained from the long leaves. At eighteenth months, pineapple leaves are cut off and the exterior green layer is scraped away using coconut shells or broken plates. The resulting fibers are organized by their thinness: finest is called Pinukpok, fine is Liniwan, and the coarsest is called bastos.

Traditional method of weaving pineapple cloth, 1899

Demonstration of modern day weaving, October 2019

Fibers are then washed and weavers conduct Pagpisi and Pagpanug ot where strands are knotted and trimmed to be prepared for spinning, followed by weaving. Once the fabric is off the loom, elaborate calados or embroidery can be included creating intricate designs seen on handkerchiefs and blouses. Pineapple cloth is used both for clothing, such as the Barong Tagalong, for domestic textiles such as table cloths and mats. The fabric has a transparent or yellow-tinted appearance, but it is also commonly dyed using vegetables, tree barks, and other regional plants. Bright yellow dye is derived from the tawa tawa, a plant often used for its medicinal purposes, or turmeric if available. Sappang and its wood create a range of colors from red to violet. Blue was obtained from the native indigo plant, malatayun. Nicknamed the “dye capital of the Philippines,” the people of the Luzon region of dyed the fabric after it was made in the Aklan provinces. Weaving in Manila allowing a cultural exchange that influenced the clothing styles. Manila, the capital of Philippines, was the center of Asian, American, and European trade routes as of the sixteenth century. Since the production process was lengthy, it increased the price of pineapple cloth, which effectively transformed it into a luxury limited to the upper-middle and elite classes. When not worn in the Philippines, the cloth was commonly given as a gift in Europe as it was prized due to the uniqueness of the fabric when compared to western textiles.

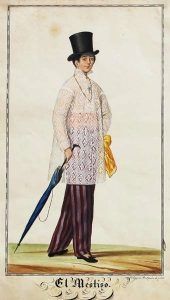

Foreign influence and colonialism changed fashions in the Philippines . Inhabitants of the island had been weaving pineapple leaf fibers traditionally long before Spanish conquest. In addition, they had combined the fibers with silk that suggests existing trade and influence coming from China. In the sixteenth century, natives referred to in Spanish as “Indios,” dressed not very modestly (as judged by European eyes) due to the natural transparency of the fabric. Elites were able to embellish the clothing pieces by layering with other Filipino and Spanish clothing.

Foreign influence and colonialism changed fashions in the Philippines . Inhabitants of the island had been weaving pineapple leaf fibers traditionally long before Spanish conquest. In addition, they had combined the fibers with silk that suggests existing trade and influence coming from China. In the sixteenth century, natives referred to in Spanish as “Indios,” dressed not very modestly (as judged by European eyes) due to the natural transparency of the fabric. Elites were able to embellish the clothing pieces by layering with other Filipino and Spanish clothing.

The women wore a sarong, collarless jacket, and a close-fitting long-sleeved shirt fastening in the front with braids or cords of silk, providing more proof of Chinese influence. The Spanish style brought fuller skirts. With piña cloth production flourishing in the areas the Spanish had Christianized, embroidery was encouraged, usually taught by nuns. Indigenous needlework practices and plant life resulted beautiful imagery, such as flowers, fruits, and coconut trees. Production of Piña was located primarily in the central Philippines and the Visayan provinces of Aklan and Ilio, as well as on Panay island. The Visayan island along the southern section of Luzon to the North also saw cloth production and dyeing of the fiber. These lowland areas were most affected by Spanish colonialism and the spread of Christianity from 1565 to 1898.

The women wore a sarong, collarless jacket, and a close-fitting long-sleeved shirt fastening in the front with braids or cords of silk, providing more proof of Chinese influence. The Spanish style brought fuller skirts. With piña cloth production flourishing in the areas the Spanish had Christianized, embroidery was encouraged, usually taught by nuns. Indigenous needlework practices and plant life resulted beautiful imagery, such as flowers, fruits, and coconut trees. Production of Piña was located primarily in the central Philippines and the Visayan provinces of Aklan and Ilio, as well as on Panay island. The Visayan island along the southern section of Luzon to the North also saw cloth production and dyeing of the fiber. These lowland areas were most affected by Spanish colonialism and the spread of Christianity from 1565 to 1898.

By the mid-nineteenth century, the sleeves of camisas were becoming more voluminous and tubular in shape. The end of Spanish colonialism through revolution saw the camisa become shorter and pañuelo became wider and higher becoming a fashion statement against the previous attempts by Spanish to encourage modesty according to conservative Spanish views.

Later, during the American colonization from 1902-1946, Filipino dress styles evolved to embody a greater political significance. Men turned to western dress in their struggle to gain political power and modernity in the face of westernization, while women wore the traditional terno and pañuelo to represent the suppressed colonized subject. This is the time period, shortly before the outbreak of World War II, during which Byers visited Manila and purchased her gown. The elaborate embroidery is considered a representation of Philippine autonomy in the face of colonization by both the Spanish and the Americans. It also coincided with the global tidal wave of modernism and westernization experienced by the people of the Philippines.

Later, during the American colonization from 1902-1946, Filipino dress styles evolved to embody a greater political significance. Men turned to western dress in their struggle to gain political power and modernity in the face of westernization, while women wore the traditional terno and pañuelo to represent the suppressed colonized subject. This is the time period, shortly before the outbreak of World War II, during which Byers visited Manila and purchased her gown. The elaborate embroidery is considered a representation of Philippine autonomy in the face of colonization by both the Spanish and the Americans. It also coincided with the global tidal wave of modernism and westernization experienced by the people of the Philippines.

The use of piña cloth declined dramatically in the early twentieth century, but in the 1980s there was a sudden revival led by Filipino designers and the Patrones de Casa Manila. The revival saw piña cloth being used in a series of couture garments that tied the fabric to a renewed sense of nationalism.

Piña cloth has acted as a popular souvenir item since the nineteenth century. According to Linda Welter’s article “Dress as Souvenir: Piña Cloth in the Nineteenth Century,” piña cloth did not become popular as a trade good, but it became a favorite memento from East Asia. Ship captains and officers purchased dress lengths for their wives because of its beauty, rarity, and exotic origins. In New England, the cloth was especially popular as a gift because pineapples symbolized friendship and hospitality. Logically, pineapples became a popular decorative element for piña cloth items. The fabric resembled the various sheer fabrics that were fashionable in the western world, and it functioned as an exotic alternative in constructing clothing and accessories.

Among the earliest examples in the United States is a French-style ballgown, last photo, made between 1804 to 1814 that was made from a piña and silk mixed fabric embroidered with pineapples along the hem. While the exotic nature of the fabric was prized, costumes from the non-Western cultures not fashionable, and most clothing made from piña conformed to the current modes.

The Cora Ginsburg 2022 Antique Catalogue provides an example of a young girl’s formal dress made of piña cloth but designed in an American style and notes that “The fabric used for this dress that is associated with the coastal town of Hampden, Maine, was likely acquired directly by a U.S. seamen who traveled to the Philippines, probably en route to China.”

The Cora Ginsburg 2022 Antique Catalogue provides an example of a young girl’s formal dress made of piña cloth but designed in an American style and notes that “The fabric used for this dress that is associated with the coastal town of Hampden, Maine, was likely acquired directly by a U.S. seamen who traveled to the Philippines, probably en route to China.”

While piña was in use in the Western world as symbol of wealth and a souvenir of travels to exotic lands, its connection to the Filipino people and islands was hidden behind Western sensibilities and styles.

Piña in Modern day Featured photo of Pia Alonzo Wurtzbach, Miss Universe 2015, is seen wearing embellished butterfly sleeves on a Terno. This was a representation of Filipino national pride during the Binibing Pilipinas 2015 Fashion Show in Smart Araneta Coliseum.

Piña in Modern day Featured photo of Pia Alonzo Wurtzbach, Miss Universe 2015, is seen wearing embellished butterfly sleeves on a Terno. This was a representation of Filipino national pride during the Binibing Pilipinas 2015 Fashion Show in Smart Araneta Coliseum.

Presently, pineapple cloth production continues in greater quantities due to the concept of sustainable fashion, which aims to find alternative textiles to reduce carbon footprints while creating environmentally friendly clothing. As the 1980s revival movement reintroduced piña cloth to the world of high fashion, modern-day designers and companies are embracing this fabric. Companies such as Pinatex use pineapple leaves as an alternative to leather. Advances in dye science has expanded the range of colors previously limited by the available regional dye plants.

Martha Moon-Renton, Kasmira Zechman, Julivette Torres

Created for the HIS 501: Applied History Interpretation Project

1910 US Census, Washington County, Maryland, population schedule, Hagerstown City, Ward 2, Enumeration District (ED) 22-11, sheet 20-B, dwelling 498, family 512, Wilbur E. Byer.

Binibining Pilipinas 2015 Fashion Show, Pia Alonzo Wurtzbach, 2015. Digital Photograph. printed 2015, 354 × 810 pixels. Link

Flores de la Rosa, Simon. QUIAZON FAMILY, c. 1880. Oil on canvas. Link

Hale, Tili. Cora Ginsburg 2021 Catalogue. Accessed October 2, 2022. Link

Milgram, Lynne B. “Pina Cloth, Identity and the Project of Philippine Nationalism,” Asian Studies Review 29, no. 3 (September 2005): 233– 246.

Milgram, Lynne B. “Snapshot: Revival of Pina Cloth and Dress: Southern Luzon and Central Philippines.” In Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion. Edited by Joanne Bubolz Eicher. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Montinola, Lourdes R. Piña. Metro Manila, Philippines: Amon Foundation, 1991.

Roces, Mina. “Gender, Nation and the Politics of Dress in Twentieth-Century

Philippines.” Gender & History 17, no.2 (August 2005): 354–37.

Slack, Edward R. “Philippines Under Spanish Rule, 1571-1898.” In Obo Latin American Studies (January 2014) Link

The Cumberland 1927. Shippensburg, Pennsylvania: Cumberland Valley State Normal School, 1927.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Depret Dress French.” Accessed October 3, 2022. Link

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Ensemble British.” Accessed October 2, 2022. Link

“Traje de Mestiza.” Philippine Folklife Museum Foundation, Accessed October 01, 2022. Link

Welters, Linda, “Dress as Souvenir: Piña Cloth in the Nineteenth Century.” Dress 24, no.1 (1997): 16-26.