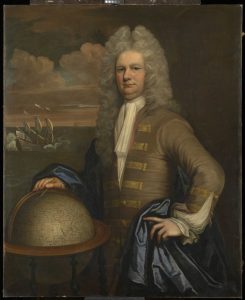

The British East India Company (hereafter abbreviated as EIC or the “Company,” was a branch of the British military stationed in the East Indies, later East Asia, from its creation in 1600 until its demise in 1874.

Trade in this region in cotton, silk, indigo, saltpeter, tea, and opium resulted in the creation of the company, which was very successful during its life, and is still considered “the most powerful corporation the world had ever known.” It controlled nearly all of the trade of British tea, for example.

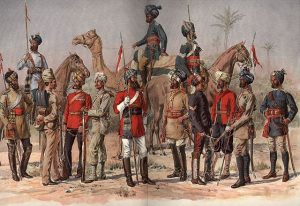

Soldiers serving in the EIC were typically not English but rather native Indians.

The Fashion Archives & Museum’s uniform is comprised of two pieces: a wool coat and a pair of buckskin breeches worn by the same man.

The buckskin was obtained in North America, however, where exactly is unknown. While the British had lost control of the American colonies at the time the uniform was worn in the 1790s, they still possessed colonies in Canada. Business ties between the United States and Britain resumed after the conclusion of the American Revolution, so an American source is also possible.

The jacket is made of British wool and is dyed shades of red and yellow. The buttons the facings are made of gilded brass and bear the emblem of the East India Company. The British had been producing Europe’s best woolen goods since the Middle Ages.

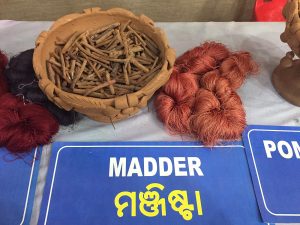

Madder Root and Madder Dyed Fibers

Cochineal Insect

Typical red dyes that would have been used in the eighteenth century came from either madder root or cochineal. These two colors would signify whether the soldier was a private or an officer.

Madder root dye tended to be more of a scarlet red and was used for private soldiers while the more expensive cochineal created a deeper crimson red and typically was used for officers. Madder was widely cultivated in many parts of the world, but cochineal production was concentrated in Central and South America, particularly in modern-day Mexico.

The lining of the jacket is made out of ivory silk twill which was produced in the Bengal region of India.

Inorganic dye did not become popular until the late 1850s which means that dyeing prior to this date was a specialized trade. The colorants were derived from plants, insects, as well as other organic materials.

As the name indicates, madder root dye came from a plant that was native to India and where the EIC resided. This made obtaining this root easier for the EIC and therefore made the dye cheaper, which is why it was used for privates rather than officers.

Cochineal dye on the other hand is produced by a female insect of the same name from Central and South America. In 1630, a Dutch dyer, who was living in England, discovered that chloride of tin mixed with the cochineal produced a deep red.

The cuffs and the lapels of the jacket are both dyed a rich yellow. Lapels of a variety of colors, also known as “facings,” were used to differentiate military regiments in the Company. India used so many colors that English officers were advised to bring multiple shades of fabric to India to match their new regiment. However, the most popular color for facings in India was yellow. Beginning in 1790, all Indian regiments were required to use yellow facings.

During the time period numerous sources of yellow dye existed across the globe. These sources were made up of various types of vegetation including plants and trees. These dye sources were not only used for textiles but for other products including food, paint, and medicine.

Yellow dyes for textiles were harvested from the weld plant in Europe, the quercitron tree in North America, saffron from India and other parts of Asia, as well as safflower from Asia, Europe and North America. While it is not possible to identify the source of the yellow dye without chemical analysis, there is a high probability that it was the spice saffron. During the time the coat was in service, it is highly likely the EIC sourced the saffron locally and used it to dye the cuffs and facings of the uniform.

The lining of the coat is made of silk.

Prior to the nineteenth century, Britain relied on the importation of raw silk.

The British silk industry suffered greatly from American textile boycotts that began in the 1760s and did far more damage than the tea boycotts. Bengal silk was the lowest quality at the time due to the coarse, unequal skeins. However, the Company realized that Bengal’s silk had to improved in order to appeal to customers and expand the market.

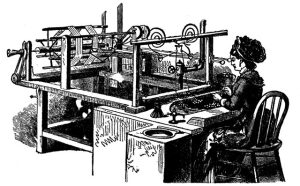

The East India Company turned to the Piedmontese reeling machine to improve its silk quality

Those working in the filatures were Bengal locals who were paid wages.

Those working in the filatures were Bengal locals who were paid wages.

The EIC did not play a role in the production of the silkworm cocoons but took control of the silk production and the trade of the finished yardage.

To understand the nature of the uniform’s significance, the scale and influence of the British East India Company as a colonial power cannot be dismissed. Formed in 1600, a century before the union of England and Scotland into Great Britain, the EIC served as an economic powerhouse in its area of operations in Southeast Asia by facilitating and controlling the trade goods Europeans coveted so dearly. In building up its power, the Company established control over India in order to procure trade goods for purchase in Europe and elsewhere. Primarily the trade interests were in silk, tea, dye, and spices among other goods that the British sought to control, both for their own profit and to compete economically with other dominant European powers who were also trying to corner their own pieces of the Southeast and Asian markets. This mass accumulation of wealth through control of the Indian subcontinent resulted in the EIC rivaling Britain itself in terms of economic, political, and military power.

To protect trade interests as well as keep order in India, the EIC began raising its own private military to manage the three areas of governance (known as presidencies between 1757-1858) that it held: Bombay, Bengal, and Madras. These presidencies were each equipped with their own armies for the purposes of enforcing the rule of both the Company and the British Empire, and these armies consisted primarily of Indian-born recruits (known as sepoys) employed by the EIC and commanded by British-born officers. Their primary functions were to enforce the Company’s policies, protect trade, and to put down any opposition to Company rule. An important factor to note about the hierarchy of the presidency armies is that no Indian soldier or officer could command a British soldier or officer even if the latter were of subordinate rank, exemplifying an aspect of the colonial apparatus that the armies protected. Primarily, the formation of the presidency armies consisted of British officers in command of Indian sepoys, another extension of British dominance over the subcontinent.

In the case of this specific uniform, it is identified as being an officer’s jacket and breeches dating to the 1790s, the revised shape of the coat being one of the primary dating factors. The distinguishing features of this jacket include an inner silk lining, gilt metal buttons, a deep red wool exterior, yellow facings and cuffs, and buckskin breeches. But what does all this mean? What is the significance of the parts of the uniform and the history of the EIC brought together? What stories do they reveal about both the Company and about British imperialism?

As mentioned previously, British-born officers often commanded EIC Indian troops. However, this structure did not preclude Indians from serving as junior officers within the presidency armies, typically as lieutenants or ensigns. British officers were not familiar with the native languages and needed junior officers to serve as interpreters and intermediaries with the sepoys in order to conduct their operations. While the original wearer of the coat and breeches remains unknown, the chain of acquisition suggests it was a British officer. With the privilege of being an officer came the expectation and possibility of affording for finer uniform materials.

Regarding the actual period of active use of the uniform, the 1790s marked the height of Company rule in India. Chronologically, it was at the midway point between the beginning of Company rule in 1757 during the Seven Years’ War and before the Indian Rebellion of 1857, which saw a mutiny of sepoys and officers against British colonialism, effectively bringing the EIC and India under the direct control of the British Empire. During the 1790s, as with the other years of its rule, the Company had to contend with rivals and dissenters who resisted British occupation and imperialist incursions. The Third and Fourth Anglo-Mysore Wars occurred during this time as a reinforcement of the strength and authority commanded by both the EIC and the British Empire. This very uniform could have very well been worn by an officer who participated in one or both of the campaigns. It is only appropriate that garments that were manufactured due to global trade and colonial rule were used in military operations to sustain aforementioned global trade and colonial rule.

This uniform represents a remarkable and transformative time in history when the British East India Company was a force to be reckoned with and the most powerful corporation in the world. With its own standing armies, its size eclipsed that even of the mother country of Great Britain and was instrumental in enforcing colonial rule not just in India, but throughout Southeast Asia and the world. This uniform’s makeup and purpose are to provide wealth and power to the wealthy and powerful, and demonstrating both what imperialism was and how it was enforced through something as seemingly simple as military dress. The global trade necessary for the creation of the uniform, worn by a British officer stationed in India, reinforced British trade domination in world marketplace.