Innovation, Endurance, and Mobility in Women's Fashion, 1860 to 1915

This online exhibit features three stories from the Fashion Archives and Museum (FA&M) that highlight the innovation, endurance, and mobility of American women through their clothing:

These three stories celebrate the innovation, endurance, and mobility of women through the clothing they wore.

This exhibit showcases clothing and paper ephemera from the Fashion Archives and Museum collection. Read along as the exhibit guides you through the intersection between historical clothing and women’s lives by considering the exterior and interior construction of the pieces and their context. You might be surprised by what you discover hidden beneath the checked and dotted silks! Our FA&M staff certainly were. Finally, please note that any pictures included in this online exhibit can be viewed in more detail by clicking on the images. Enjoy!

Our first tale begins with this set of two bodices and an overskirt (S2009-06-007, FA&M Purchase), worn by a young woman who lived during the 1860s and 1870s. The brown and white checked silk bodice pictured by itself on the mannequin at right was made in the 1860s. The second bodice, pictured on the fully dressed mannequin, is from the 1870s, along with the checked overskirt featuring an asymmetrical triangular design of brown silk ribbons. These pieces arrived at the FA&M in 2009, when they were catalogued as a young woman’s blouse from the 1860s, with an additional, ruffled bodice and overskirt made at a later time. (Note that the brown, pleated underskirt is a modern reproduction made by a volunteer to replace the missing underskirt.)

Since 2009, these pieces have resided safely in the FA&M collections storage. However, during the course of preparing these pieces for the Spring 2021 exhibit, interns at the FA&M (Drew, Shawn, Peyton, and Lonna) could not fill out the bodice on a mannequin with the usual petticoats and padding. Eventually, the interns discovered the source of the issue–the 1870s bodice was a young woman’s maternity bodice, and not simply a garment made at a later date! The young woman who wore these garments most likely became pregnant around or just before 1873-75. She used the original 1860s skirt, supplemented with dark brown silk (perhaps from a previous underskirt), to create her new bodice and overskirt. The new bodice and overskirt’s embellishments and ruffles, especially the large pocket, were fashionable details for the 1870s, stylishly adorning a gown constructed to accommodate her changing shape. Through this young woman’s innovation, she designed a new dress from the old, a thrifty move that allowed her to actively engage amongst friends and family or in public.

Women in the nineteenth century often concealed their pregnancies, rarely discussing childbirth in the public sphere or writing about their experiences. Childbearing was a dangerous, often tragic experience for women. Most births occurred at a woman’s home, and women faced the possibility of long and painful labors, devastating infections, and the knowledge that they and their baby might not live through the experience. Because of these realities, garments were altered into maternity wear to fit women’s growing bodies and then quickly altered back following pregnancy, either by the woman herself or other women. Women also wore loose-fitting gowns, called wrappers, for work at home or when pregnant (Wass & Webb). Due to this, historical maternity gowns are not always easily identifiable, especially high-fashion gowns, since a gown with a loose shape enabled free movement during work, or comfort and concealment during pregnancy.

While we do not know the identity of this dress’s owner, we can surmise some details from her garments. The 1860s bodice (pictured by itself on a mannequin) is fully lined and boned, creating a structured, hourglass silhouette; it features low-set armscyes popular during the period, with ruched self-fabric puffs on the upper arms and modified pagoda, or demi-wide pagoda, sleeves. Despite an aura of silence surrounding pregnancy, this young woman’s maternity bodice (shown with the overskirt) reflects the latest trends of 1873 to 1875, meaning she most likely created her bodice with the public eye in mind. Her maternity bodice, with its rounded basque shape, reflects an 1870s style. Dark brown frills create a decorative V-neckline along with the standing checked ruff over a short collar. The 1860s to 1870s overskirt, with its asymmetrical and triangular lines, is striking with its parallel rows of bold brown ribbon and wide ruffles. This young woman was both innovative and practical–the ten brown bodice buttons were reinforced with hooks and eyes to alleviate pressure across her growing stomach, while a large pocket provided space for personal items while out and about.

The young woman’s 1870s maternity bodice surprised the FA&M staff, who would not have known the garment’s full purpose without filling it out on a mannequin for the Spring 2021 exhibit. Maternity bodices, among other maternity garments, are rare to find intact, as women often altered their maternity clothes to fit their pre-pregnancy silhouettes. However, other examples of fashionable dresses altered for maternity wear do survive, such as this 1840s gold, brown, and purple striped silk dress (S1988-13-002, donated by Friends of the Fashion Archives). This 1840s dress features a bodice cut in a V-shape, quite fashionable at the time in addition to the striped silk pattern and colors. However, at a later date, the dress was altered to accommodate a pregnancy: darts at the front side of the bodice were let out and the skirt was lengthened at the front to mitigate hem lift with a changing stomach during pregnancy.

While a young woman fashioned the 1870s checked maternity dress from one of her earlier 1860s dresses to accommodate her pregnancy, the 1840s dress was altered to accommodate pregnancy at the time. Both of these dresses reflect the innovation and mobility of women during the mid-eighteenth century who, despite societal reluctance to dwell on women’s pregnancies, repurposed their garments to allow for fashionable, purposeful engagement in public.

Our second tale explores the life and wedding dresses of Lydia Luelle Conn, pictured below (S2011-20-002, donated by J. Stevenson). Lydia Luelle Conn was born in 1868 (or 1869) in Springfield, Missouri, to parents David Conn, a farmer, and Elizabeth (nee Chambers) Conn, who hailed from Pennsylvania prior to Lydia’s birth. Lydia had at least ten siblings by 1880. By 1893, Lydia was living in Butte, Montana, one of the American West’s most famous mining boomtowns. Due to the Commerce Department Building fire of 1921, much of the United States Census of 1890 is lost; how or when Lydia Luelle Conn traveled from Springfield, Missouri, to Butte, Montana, is unknown.

Butte, Montana, of the 1890s was diverse, with immigrants and travelers drawn to its hub of miners and successful copper production. By 1900, the U.S. Federal Census reveals that Lydia lived on a street filled with neighbors who hailed from or whose parents were born in the following locations: Alabama, Colorado, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, Missouri, Nebraska, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Canada, Denmark, England, France, Germany, Ireland, Scotland, and Sweden. American Indians in Montana lived on six established reservations by 1890 and numbered over 11,200 people. This advertisement from the October 1908 The Ladies’ Home Journal (S2009-07-016) showcases the interest in moving west to states such as Montana for new opportunities.

By 1893, Lydia Luelle Conn had migrated to Butte, Montana, from Springfield, Missouri, and on July 17, 1893, she married Fred Albert Parlin, her first husband. Fred A. Parlin was born in Boulder, Colorado, on March 14, 1870, and had worked as a farmer as an adolescent. Lydia was 24 when they married, and Fred was 23.

We might assume that Butte, Montana–so distant from fashion-forward havens like New York City, Boston, and Philadelphia–was behind in the latest fashion trends. However, Lydia’s 1893 wedding dress proves otherwise; the silhouette and details of Lydia’s first wedding dress (S2011-20-001, donated by J. Stevenson) were elegant, in-style, and quite fashionable. During the nineteenth century, wedding dresses usually reflected current fashion trends; brides may have worn their best dresses or purchased new ones, but they were usually not white (Stamper & Condra). Lydia’s 1893 wedding dress is made of a light greenish-tan silk with sprays of tiny brown flowers. Beneath the skirt’s silk layer is a second layer of tan glazed linen and cotton with a corduroy hem binding. By the 1890s, bustles had fallen out of fashion, replaced with a soft fullness at the back of the skirt. Lydia’s wedding dress features a minimal train and two self-fabric ruffles. The bodice showcases the popular leg-o-mutton sleeves, which were fuller and droopier in the early 1890s before reaching their full height and structure by 1896. The bodice of this dress features the popular fabric panels that are gently folded and tucked into the waist, creating a puffed look. The self-fabric sash of Lydia’s dress, which features a ruffled rosette, emphasizes a slender “wasp waist.” Soft lace trim adorns the high neckline and sleeve puffs.

Women of all shapes and sizes dressed fashionably in the 1890s; they sought to achieve a popular shape or silhouette rather than size, often wearing padding to match the popular shape of the period. Corsets and boned bodices provided structure for a woman’s body. Lydia’s wedding dress bodice, with its interior structure shown below, contains nine pieces of boning, anchored by silk herringbone stitches. The bodice closes with fifteen hooks-and-eyes. Corseted, Lydia’s waist was 22 inches. Note the delicate pale pink seam binding, an intricate detail only present inside the garment, showing the elegance and attention to detail given to this bodice.

On March 18, 1894, Lydia Parlin gave birth to a daughter, Hazel Emma Parlin. By 1896, Fred Parlin was working as a policeman in Butte, Montana. On the night of March 18, 1896, Parlin investigated a drunken fight near Wyoming Alley, just off East Porphyry Street, when he was shot through the head and killed. The newspaper The Butte Miner describes Parlin as having been shot through the head by a man named R. P. Judge, who supposedly shot himself after. The event was well documented in various newspapers of the Butte-Silver Bow area and the wider Anaconda area. Fred Parlin was buried in Mount Moriah Cemetery in Butte, leaving behind a widowed Lydia and their two-year-old daughter, Hazel.

A little over a year after her husband’s death, on July 9, 1897, The Anaconda Standard announced that the recently widowed Lydia Parlin had been installed as an officer of the Silver City Hive No. 3 Ladies of the Maccabees (L.O.T.M.), a woman’s auxiliary branch of the Fraternal Order of the Knights of the Maccabees, a social benevolence association through which men could pay membership fees to support widows and children as an early form of life insurance. The Knights of the Maccabees was a fraternal organization, formed in Canada in 1878, that spread into the northern midwest territories from Michigan. By 1894, 33,500 members of the 157,019 Order of the Maccabees members were women; some of America’s earliest business women stemmed from the Ladies of the Maccabees’ auxiliary groups, called “hives.” It seems that Lydia had found a system of social support to help her overcome her loss.

In this same year, The Butte Daily Post issued an article titled “Mrs. Fred Parlin Said to Be in Bad Circumstances,” in which a group of twelve men implored the judiciary committee of the Butte city council to provide money “out of the city coffers” so that Lydia Parlin could buy a small house and earn a living, as Lydia had a recent bout of rheumatism and could not work, and that Fred had left her no property. From July 15, 1898, to March 15, 1899, Lydia worked as a janitress, or female janitor, at the Monroe School in Butte; both men and women were employed in this profession in Butte at this time.

By 1900, the U.S. Federal Census listed Lydia Parlin as the head of her household at 484 Park Street. Two daughters are listed beneath her name: Hazel E. Parlin, age 6, and Ida M., born in 1898, two years after Fred Parlin’s death. By that same year, Lydia had risen to the position of Lady Commander, or leader of her local L.O.T.M. hive. Despite being a single, widowed mother in Butte, Montana, during the late 1890s, Lydia Parlin seems to have endured through her social status, work, and membership in a fraternal organization. One can only wonder if she was motivated to become a Lady of the Maccabees after facing such financial strain and loss from being a widow.

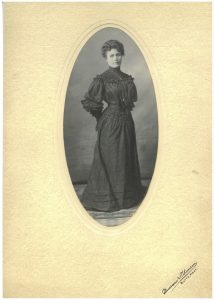

Lydia Ireton, 1906, in second wedding dress. Photography Studio of Dusseau & Thomson (FA&M Collection).

On March 29, 1906, Lydia Parlin married her second husband, Robert Ireton, in Helena, Montana, thirteen years after her first marriage. Robert Ireton, born in 1868 in Moosomin, Northwest Territory, Canada, had established himself as a successful stationery engineer employed at a Butte mine. Lydia Ireton, shown above wearing her two-piece, black silk taffeta wedding dress (S2011-20-002, donated by J. Stevenson), emanates elegance and style in the photos from her second wedding. Bodices and sleeves of 1905 to 1907 saw a slight resurgence of 1890s shapes; note how the sleeves of Lydia’s second wedding dress mirror the puffed sleeves of her first wedding dress. These 1906 sleeves, however, feature “tiers” of various puffs, ruffles, and lace, with the sleeves ending in black silk ribbon decorated with French knots and lace trim. The second wedding dress’s bodice also features a puffed breast look, with the sheer silk taffeta puffing slightly over the waist, emphasizing the “S-bend” silhouette popular at the time. Other features of this stunning bodice highlight style elements of 1906, including the wide, machine-made lace yoke the covers the shoulders, with the lace rising to a high-necked, standing collar. Finally, the bodice features a built-in, pleated waistband that fastens at the front.

The skirt of Lydia’s second wedding dress features a popular trumpet or umbrella shape of the period, with the front of the skirt falling straight and the back extending in a minimal train, usually from the use of gores in the skirt. The skirt’s top layer is made of a sheer “dotted” black silk taffeta, and the underskirt features a knife-pleated flounce. Five rows of shirring at the hips and three horizontal pin tucks at the bottom near the hem add additional visual interest.

Lydia Ireton’s second wedding dress is the epitome of elegance, with its many exterior details coming together to create a stunning whole. However, the interior structure of the bodice is just as complex. Edwardian fashion (late 1890s to 1914) had a penchant for layering closures upon closures, ensuring security for the wearer and a proliferation of fine detail. Lydia’s second wedding dress showcases this. Forty-four hooks and eyes adorn the dress. Hooks and eyes at the bodice’s left side open to reveal a corset-like boned bodice (11 bones), as well as stiff fabric ruffles that act as padding, creating a puffed, “pigeon-breasted” look.

What may intrigue some the most about Lydia Ireton’s second wedding dress is its color. The Victorian Era, from 1837 to 1901, is infamous for the Victorian “Cult of Mourning,” or the elaborate, structured cultural practices through which people grieved lost loved ones. These practices included clothing etiquette, such as wearing black for specific periods of time before transitioning through different stages of adding color into a wardrobe once more, and forgoing lively social practices. Queen Victoria dressed in mourning attire for her deceased Prince Albert from 1861 until her death in 1901 (Stamper and Condra). These mourning practices extended into the Edwardian Era, finally losing momentum after World War I.

Mourning practices dictated that a widow wear mourning clothes for two years in various stages, from wearing relatively plain, black clothes, to eventually adding in jewelry and more color. Lydia’s second wedding dress, worn ten years after her first husband’s death, raises some interesting questions. The dress is both fashionable and elaborate for the time, suggesting that Lydia–if she was wearing black for widowhood–wished to appear in-style. Did she wear black because she was a widow, in memory of her first husband’s tragic death? Mourning attire was a social symbol. What she emphasizing her social status and past in the eyes of the public? While we cannot know Lydia Ireton’s thoughts, one impression is clear: Lydia Ireton, as shown through her wedding photographs and the second wedding dress she wore, cut an elegant, impressive figure, in-style against the backdrop of Butte’s diverse mining culture.

Through the tragedy of her first marriage, her esteemed status as a Lady Commander of the Order of the Maccabees, and her fashionable approach to dress, Lydia Luelle Conn Parlin Ireton is an example of a woman who both endured and advanced socially. By 1910, Lydia and Robert Ireton moved to Skagit, Washington, where Robert worked as a foreman in a quarry. Lydia’s daughter, Hazel (from her first marriage), was quite a socialite, graduating with a music degree in 1915 from the University of Washington, Seattle, although no mention of Lydia’s second daughter, Ida, appears after 1900. Lydia Ireton passed away in 1926 at the age of 57 or 58, and she is buried in Acacia Memorial Park alongside her second husband, daughter Hazel, son-in-law, and granddaughter.

The fashionable woman who owned the garment behind our third tale is Anne Davie Guerrant, born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1879, to a prominent Louisville family. Her father, Edward Owings Guerrant, had served on the staff of General Humphrey Marshall during the Civil War; after the war, he became a doctor, writer, and Presbyterian minister, eventually opening a home for unwed mothers in Louisville in 1895. On October 19, 1905, Anne Guerrant married Norvin English Green, also of Louisville; according to the U.S. Federal Censuses, Norvin went from being a bookkeeper (1900), to a foundry secretary (1910), to the president of a car wheel company (1920). By 1920, Anne and Norvin Green had four children: Norvin, Anne, Ruth, and Mary Caroline.

The Guerrant family owned orange groves in Umatilla, Florida. As a woman and young mother of two in her thirties during the 1910s, Anne Guerrant Green drove from her family home in Louisville, Kentucky, to Umatilla–a trip of over 800 miles! While motorized vehicles had been in use prior to 1900, it was not until Henry Ford produced the classic Model T that the automobile age truly kicked into gear, with the U.S. quickly outpacing other countries’ automobile production.

Anne Guerrant Green remained in the Louisville area and was active in her Presbyterian community. Her daughter, Anne G. Green, became a prominent artist and sculptor, and her son, Dr. Edward Putney Green, opened a prominent practice. Anne Green died in 1979, aged 92, and is buried in Cave Hill Cemetery.

A woman who drove over eight hundred miles from Louisville to Umatilla in the 1910s (possibly with her children) deserved a driving duster as dashing and daring as she was! Anne Guerrant Green owned and wore just such a duster, designed by Henriette Favre of Paris and worn by Anne from 1909 to 1913. Dusters, or long coats, were worn by men and women to protect clothing from mud and dust while traveling; they were often made of linen. This duster, made of tan silk, is part of the FA&M Spring 2021 Exhibit. The design of the duster–including wide lapels, a cutaway waist, wide cuffs at the sleeves, and braided cording–is reminiscent of high fashions of the 1790s, a popular aesthetic in women’s clothing during the 1900s-1910s. The wide lapels feature horizontal tucks. A minimal collar and two tassels of black silk beneath the cutaway waist add contrast and style. The back of the duster features three tails, with the middle one accented by two rows of seven self-fabric buttons and cording. The duster is also lined in silk.

Not much is known about the designer of Anne Guerrant Green’s duster, Henriette Favre; only a handful of her designs appear to be extant, located in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s costume collection (and, of course, at the Fashion Archives and Museum!). By 1900, Favre appears to have had a storefront at 5 Rue de la Paix, Paris. Her designs were imported to the United States through Wanamaker’s, the famous department store started by John Wanamaker in Philadelphia in 1876, with a storefront opening on Broadway in NYC.

In 1897 and 1898, Wanamaker’s advertised in newspapers across the east coast for its “Exhibition Days,” where designs from elite European designers were showcased in the Manhattan Wanamaker’s store. These advertisements (including the two shown above) reached New York City’s The Sun, The New-York Tribune, The New York Times, The Brooklyn Citizen, and The Brooklyn Eagle; Wilmington, DE’s The Morning News; from Pennsylvania’ Pottsville’s The Pottsville Republican; Allentown’s The Morning Call; and Reading’s The Reading Times. According to these papers, Favre’s client list by 1898 included the Princess of Wales (the future Alexandra, Queen of the United Kingdom), the Duchess of Devonshire, and other women from English Court. Henriette Favre was included amongst such fashion designers as the House of Worth from Paris, the House of Paquin from Paris, the House of Drecoll from Vienna, and the House of Doucet. Favre had established herself as a premiere designer by 1900; in 1902, she once more dressed Alexandra of Denmark, Queen of the United Kingdom from 1901 to 1910. While we do not know where Anne Guerrant Green purchased her extraordinary duster, it may be evidence of Favre’s enduring appeal to women seeking couture items that suited an evolving American lifestyle.

Driving in the 1910s was an exciting and novel leisure activity or sport for those who could afford automobiles, although driving also functioned as means of transportation. Driving on unpaved roads in automobiles without an enclosed structure could be dusty, windy affairs. Women and men who drove needed functional accessories to tackle the open road, such as goggles, hats, and gloves.

Take a look at this motoring bonnet, shown above, worn by Helen Besore Hoover from 1907 to 1919 (S2010-23-045, donated by Schwuchow). Like Anne Guerrant Green’s driving duster, this motoring bonnet is made from tan silk. The motoring bonnet features built-in goggles embroidered into a flap to protect the wearer’s eyes from dust and dirt during a drive. The soft bonnet provided room for Helen Hoover’s hairstyle. Helen Besore Hoover was born in October 23, 1882, and died on February 16, 1971. She married Dr. Percy D. Hoover in 1907, and together they lived in Waynesboro, Pennsylvania. Helen Besore could have worn her motoring bonnet while driving or on drives with her husband, Dr. Hoover.

Our final Fashion Archives and Museum piece to share with you in this online exhibit is this pair of heeled boots from 1910 to 1911 (S1985-67-001, donated by Mrs. S. Diehl), shown below. Any woman driving on the open road needed sturdy shoes, and these stylish boots would have looked quite fashionable worn alongside Anne Guerrant Green’s duster and Helen Besore Hoover’s motoring bonnet. These black and brown leather boots feature sixteen mother-of-pearl buttons. Note the mother-of-pearl button hook in the first image; button hooks, used to catch and pull buttons through buttonholes, were household necessities during the 1890s to 1910s. These boots, with a 2 3/4 in. heel, have significant wear to both soles, suggesting that they were well worn and loved (perhaps on driving adventures!).

Women like Anne Guerrant Green and Helen Besore Hoover may have felt a sense of empowerment when they donned their driving dusters and climbed behind the wheels of their automobiles. During the 1910s, more women sat behind the wheel–and were targets of advertising campaigns! Women in the United States began driving before they could even vote, a right that some women would not have until the 19th Amendment in 1920. It is exciting to consider how world-famous designers such as Henriette Favre fashioned such exquisite garments for women who wore them while engaging in a growing sphere of social, mobile activities.

This exhibit has highlighted clothes from the FA&M collection that showcase the innovation, endurance, and mobility of women from the past. We do not know the name of the young woman who fashioned her own maternity bodice in the 1870s. We cannot know for sure Lydia Parlin’s motivations behind wearing black for her second wedding. And we do not have Anne Guerrant Green’s words to express how she felt during her long drives to Florida. But these historical garments do allow us to investigate the context of these women, the physical spaces that they inhabited, and the garments they wore as forms of self-expression–garments both practical and in style when they were worn. These garments illuminate the joys and sorrows women experienced, the social statuses they held, and the social activities that filled their lives.

Bibliography

Anderson, Margaret. “19th Century Childbirth.” Adelaidia. December 11, 2013. Link.

“Automobile History.” History. August 21, 2018. Accessed May 19, 2021. Link.

Bohleke, Karin J. Nineteenth-Century Costume Treasures of the Fashion Archives and Museum: 1800-1900. Shippensburg University Fashion Archives and Museum, 2010.

“Butte Current Notes.” The Anaconda Standard, vol. 8, no. 310, July 9, 1897, 5.

“Butte in Brief.” The Butte Miner, vol. 43, no. 259, April 20, 1906, 6.

“Condition of the Montana Indians in 1890.” AccessGenealogy. Accessed May 19, 2021. Link.

Creighton, Margaret S. The Colors of Courage: Gettysburg’s Forgotten History: Immigrants, Women, and African Americans in the Civil War’s Defining Battle. New York, New York: Basic Books, 2006.

“Guerrant, Edward O. (Edward Owings) 1838-1916.” OCLC WorldCat Identities. Link.

“Guerrant-Green Marriage.” The Courier-Journal, vol. 104, no. 13,441, October 19, 1905, 4.

Meredith, Milo.”The Order of the Maccabees.” [Pamphlet.] Wabash, Indiana: 1894. Accessed through the U.S. National Library of Medicine. Link.

“Miss Hazel Parlin.” The Anaconda Standard, vol. 26, no. 283, June 13, 1915, 24.

“Night of Bloodshed.” The Butte Miner, vol. 23, no. 78, March 18, 1896, 1.

“Notice! Silver City Hive No. 3, L. O. T. M.” The Anaconda Standard, vol. 12, no. 22, October 2, 1900, 9.

O’Brien, Alden. “Motoring,” in “Fashioning the New Woman: American Women and Fashion, 1890-1925.” [Exhibit pamphlet.] Washington, D.C.: National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution, 2012, 25.

“Retained the Check.” The Butte Miner, vol. 25, no. 196, July 15, 1898, 5.

Stamper, Anita, and Jill Condra. Clothing through American History: The Civil War through the Gilded Age, 1861-1899. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood, 2010.

“To Relieve the Widow.” The Butte Daily Post, April 8, 1897.

Wass, Ann Buermann, and Michelle Webb Fandrich. Clothing through American History: The Federal Era through Antebellum, 1786-1860. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood, 2010.

Images from Outside the FA&M Collection

Detroit Photographic Co., Publisher. An Indian River Orange Grove, Florida. United States Florida, 1898. Detroit, Michigan: Detroit Photographic Co. Photograph accessed from Library of Congress. Link.

General view of the diamond mine of Butte, Montana. Butte Montana, 1905. Photograph accessed from Library of Congress. Link.

“Paris, France. Rue de la Paix decorated for Theo Roosevelt.” 1910. Photograph accessed from the Library of Congress. Link.

Price, Albert M., photographer. Orange grove, Florida, grandmother eats an orange. Between 1914 and 1929. Photograph accessed from Library of Congress. Link.

Rau, William Herman. Broadway and Montana Sts. of Butte, Montana, during great September fire of 1905. Butte, Montana, ca. 1905. Philadelphia: William H. Rau. Photograph accessed from Library of Congress. Link.

Rau, William Herman. Walkerville, a suburb of Butte, Montana. Walkerville Montana, ca. 1905. Philadelphia: William H. Rau. Photograph accessed from Library of Congress. Link.

“The Order of the Maccabees.” Wabash, Indiana: 1894. Pamphlet accessed through the U.S. National Library of Medicine. Link.

Acknowledgements & Credits

The following individuals supported this online exhibit in various ways: Volunteer Lisa Maier sewed the reproduction underskirt featured on the 1860s maternity dress and provided conservation sewing on Lydia Parlin’s wedding bodices. Volunteer Joann Dunigan provided conservation sewing on the 1910s Henriette Favre driving duster. Student interns and volunteers, including Drew Ceneviva-Holder, Shawn Pokrop, Peyton Bramble, Abigail Koontz, and Lonna June Anderson, arranged and filled out the historical garments on mannequins.

Photographers include: Barbara Hunt, who photographed the 1860s maternity piece and Lydia Parlin’s second wedding dress; Lonna June Anderson, who photographed Lydia Parlin’s first wedding dress, second wedding dress details, and driving accessories; and William Smith, who photographed the 1840s maternity piece in 2010.

Special thanks to: Dr. Karin Bohleke, Director of the FA&M, for answering countless historical costuming questions and for assembling the Committee of Good Taste; Joann Dunigan, for making excellent coffee; Kim Murphy Kohn at the Butte-Silver Bow Public Archives, who was so helpful in providing initial research assistance on Lydia Parlin; and Lisa, who mined the depths of Ancestry.com with me (what happened to Ida?) and provided conservation sewing for the lace on Lydia Parlin’s first wedding dress.

Abigail S. Koontz, Graduate Student, MA in Applied History, SU Spring 2021 Semester