What influence do you think a hat could have on the world? Do you think about fashion, celebrities, maybe the baseball hat you wear on a sunny day or the knit cap you use to keep away the cold hanging in your closet? What about the origins of the hats you wear, the evolution of the styles that lead to modern hats, or the effects on the people who were creating these hats? When you think about top hats in particular, you probably think about popular representations of top hats, pictures of president Abraham Lincoln, the Mad Hatter chasing the March Hare, or even the Monopoly box you may open to play with your family. You probably do not think about international relations, governmental reform, global trade, and economic competition that spurred global exploration, and started and averted wars, but the hat played a role in all these things.

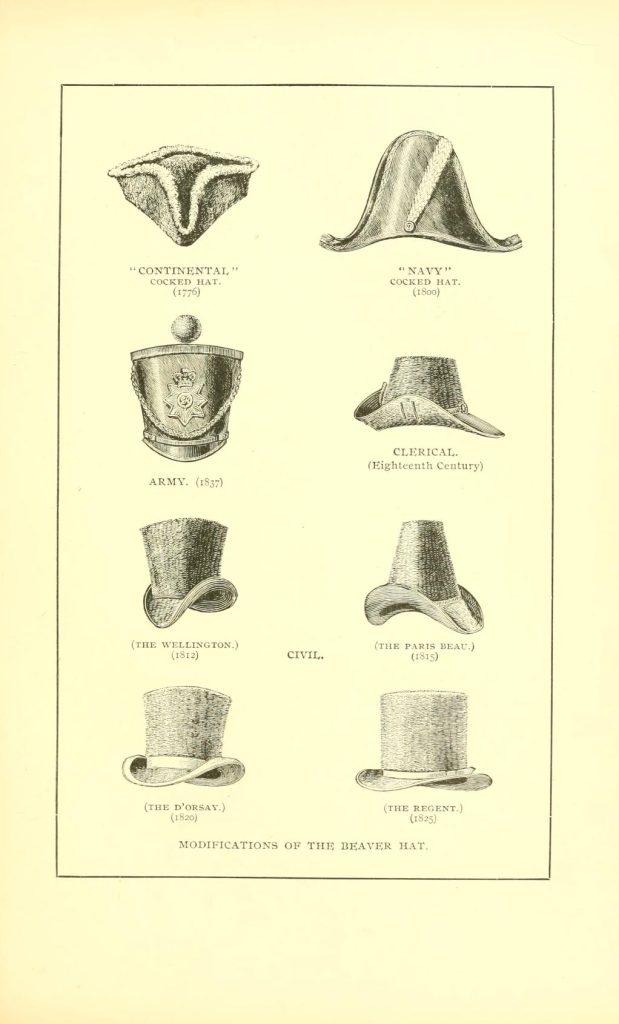

Felt hat making originates as far as the seventeenth century in Europe. Before the popularity of the top hat, furs were used to create many different styles of hats, from styles known as “Continental” to “Navy” hats. Beaver hats boomed in popularity in the 1600s, when England’s King James I ordered twenty beaver hats in 1603; “17 of them were to be black, lined with taffeta, trimmed with black bands and feathers.” While the top hat was not yet invented (though its stylistic origins date back to the Capotain hats of the 1600s), the beaver felt hat would become popular for upper class peoples, and at the time was an inexpensive accessory for high class fashion to show nobility and wealth.

The massive popularity of the beaver hat significantly increased the scale of hunting and trapping beavers in Eurasia. Tariffs in 1600s Europe made imports from the Americas expensive and undesirable, instead heavily focusing on the high quality furs in Europe. The over-hunting of European beavers led to their near extinction, and by the 1800s, European beavers were no longer suitable for hunting due to the low numbers. Furs would have to be sought elsewhere.

Several styles of beaver hats, from Continental to “The Regent,”

as depicted by Horace T. Martin in Castorologia.

By the 1800s, with European beavers virtually extinct, most beaver fur trapping came to the United States and Canada. Several massive fur trapping companies, such as the aptly named American Fur Company, contributed to the collection of thousands of pounds of beaver furs annually from 1800 and into the 1840s. Soon, overhunting destroyed the beaver population in North America just as it had in Europe. The price of beaver furs and beaver top hats rose dramatically due to the dwindling North American supply, making consumers desperate for a cheaper but suitable alternative.

With the loss of the beaver supply, combined with the high demand for top hats, hatters moved to different materials that were more widely available. With sericulture (silk) farms producing hundreds of tons of silk in Europe, along with increased trade from Asia, using raw silk was a simple alternative in the mid-19th century, surpassing beaver fur as the primary material for top hats. European and American industries had already expanded the process of refining silk through massive looms and tightly weaving the silk into woven fabric, and now the technology could be applied to top hats.

“… on the public highway, wearing upon his head a tall structure having a shiny lustre and calculated to frighten timid people … Several women fainted at the unusual sight, while children screamed, dogs yelped and a younger son of Cordwainer Thomas, returning from a chandler’s shop, was thrown down by the crowd which collected and had his right arm broken.”

-January 24th 1899 Huddersfield Chronicle

The top hat–also known as the Stovepipe hat, Plug hat, Chimney-pot hat, and many others–was the premier fashion accessory of the nineteenth century. Preceded by the pointed tricorne and bicorne hats as well as wide brimmed and flat caps, the top hat came as a stark contrast to the elaborate and colorful headwear of previous centuries. Costume historian Madeline Ginsburg’s gives a succinct description of the hat’s identity in the nineteenth century, “The top hat is considered to convey authority and ambition, its shape to be a monument to the chimneys of the industrial revolution.” The top hat’s shape developed as the political and social landscape changed at the end of the eighteenth century and into the start of the nineteenth. In France in particular, the mix of royal loyalist ideas and revolutionary sentiment saw the movement away from the high society capotain, tricornes and bicornes, in favor of the revolutionary hats of the people, namely the Phrygian hat (liberty cap or “bonnet rouge”) and the ribbon cockade. This period furnishes an excellent example of how clothing people wear and the accessories they don to express themselves provide a close look into their beliefs and the norms of their time.

The top hat’s style and usage evolved throughout the nineteenth century as it shifted from summertime usage, to the correct dress of the upper classes, to a hat for everyman and every occasion, and then to formal and evening wear. The material of the top hat in the first few decades of the 19th century was indicative of the cost and thus the social status of the wearer. The most expensive were made of pure beaver felt, giving a dark brown or black color after treatment and polishing. Other fur felts were sometimes used with a top layer of beaver at a lower cost and having a definite difference in appearance. Straw was also a material used in warmer climates and at low cost.

The early top hats were tall and wide brimmed, this appearance would garner them their nicknames of stovepipe and chimney as their flat wide brim contrasted their tall, straight and flat top. Over time, the brim shrank toward the head, conformed more to the shape of one’s head, and lost a few inches in height. The middle of the nineteenth century witnessed more variations in designs and styles. Hats began to taper and flare at the top, the brims widened, and the height became either longer and thinner or shorter and wider. The top hat was becoming a part of everyday apparel and spreading to the middle and lower classes. This variety in shape as well as increased availability was due to the change in material to silk, which allowed a much glossier and more lustrous appearance that rivaled the heavily polished and laboriously maintained felt versions. According to John Peacock, the top hat appeared in the daily wear of people from 1806 until the beginning of the twentieth century, when it was definitively relegated to formal and evening wear. The color of the top hat was black in most cases with a few styles appearing over the nineteenth century in brown, white, and beige, and a gray top hat was also present after the transition to silk. The top hat was worn always in tandem with a coat, whose shape, color, material, and style evolved over the century.

The top hat’s reign as the quintessential headgear of the nineteenth century was not without trials and tribulations resulting from its bulkiness as well as its uncomfortable weight. The numerous layers of felt and later silk along a supporting frame made it difficult to store and carry. The hat was also high maintenance. The brims were regularly damaged through use and the felt often tore or thinned along the flat top. Hatting in the nineteenth century also followed the trend of recycling hat materials and thus led to dubious quality amongst cheaper felt versions as the felt was used numerous times and brims were attached to existing tops. A response to the bulkiness and battered nature of the top hat was the opera hat, which was nearly identical and thus had its origins in the top hat but differed in its structure. The opera hat was a top hat but with an unstiffened body and flexible ribs connected to springs, allowing the hat to collapse flat and easier to handle. The opera hat had its own difficulties in maintenance and repair, but it rivaled the traditional top hat after its invention.

Once a beaver fur is collected, the process of making the beaver felt hat begins with removal of the fur from the beaver hide. The beaver hide has two layers of fur: the top layer is made up of individual strands, called guard hairs; the bottom layer is a softer material known as underfur. In the refining process, the course guard hairs must be removed and discarded from the underfur. The underfur has microscopic barbs that help the individual strands of underfur stick together, and when tightly combined together, makes beaver felt. However, these barbs stay closed even after being removed due to a protein called keratin in the fur, making the felting process initially impossible. In the early eighteenth century, however, the process called “carroting” was established; hatters and felters used chemicals to open these barbs, including nitric acid or even mercury-based chemicals. Other methods were attempted, but resulted in a loss in fur quality.

After collecting and treating the underfur, the hatter cleaned any dirt or other debris through a process called “bowing,” which entailed using an archer’s bow-shaped string to separate debris while also promoting bonding and even distribution of the fur. The remaining fur mat was pressed and steamed with hot water and/or other mixtures, such as urine or wine sediment, to bond the hairs further and form the felt mat. At this time, the hatter began to form the hat’s shape, albeit much larger than the finished product in this early state. After applying continuous pressure and dipping the felt in these heated mixtures, the felt shrank and created a stronger bind, making it near impossible to pull apart by hand. Upon completing the shrinking process, the felt was shaped on a wooden block, and the brim trimmed as needed.

Example of a 1790s beaver felt hat. Characteristics, such as the indent on the top of the hat, along with the uneven brim, show early attempts at perfecting the top hat.

Silk hats had different refining processes, but used similar steps to shape the hat itself. The silk is first collected from the fibrous cocoons of silkworms, which were fed mulberry leaves prior to making the cocoons. Cocoons are boiled to remove any larvae in them, and the end of the silky filament of the remaining cocoon is woven on a reel. Additional “threads” of silk filaments are added to the reel and twisted together, making the silk stronger and larger, enough to place the silk yarn into a loom. The silk yarn is woven with a loom, turning the silk into a uniform textile ready to be shaped. At this point, the silk is no longer considered “raw.”

Before silk is added to the hat, the shell of the hat is first made with several layers of gossamer, which is a thin layer of woven fabric (which can be silk or another material such as cotton). Once the shell of both the brim and the hat are connected and hardened on a wooden hat block, the fully woven silk fabric is stitched on top of the shell, giving the finished look. Additional stitching and lining, usually dependent on the hat’s manufacturing company, is then added to the hat’s interior to ready it for sale.

Example of a 1880s top hat. Clear changes from the 1790s hat, such as a much sturdier brim and stronger general shape, due to the different hat making process from beaver felt to silk.

The hat-making process was fraught with hazards. “Carroting,” as explained earlier, processed the furs using mercuric nitrate, which introduced dust covered in this chemical into the air. The steaming process to shape the fur led to a further release of this chemical into the air. The hat makers over the course of their careers developed mercury poisoning. The typical symptoms of long-term organic mercury poisoning include tremors, unsteady walk, double or blurry vision, memory loss, and seizures. This coupled with quenching the thirst created by inhaling dust and fumes with alcohol gave a sound basis to the phrase “mad as a hatter”.

The Hatter character from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, 1865. Illustrated by John Tenniel.

Alice in Wonderland certainly popularized the phrase “mad as a hatter” through the eccentricity of the hatter character. However, the first recorded use of the phrase actually dates back to 1829 in Noctes Ambrosianae, a fictional colloquy by John Wilson published in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine. In this conversation, set in Ambrose’s Tavern in Edinburgh, the character Christopher North launches a monologue about the preparation of various beverages and his time in Africa. Three other characters, Timothy Tickler, Ettrick Shepherd, and Morgan O’Doherty have a side conversation saying,

“Tickler (Aside to Shepherd) He’s Raving

Shepherd (to Tickler) Dementit.

O’Doherty (to both) Mad as a hatter. Hand me a segar [cigar].”

The next recorded use of the phrase comes from The Clockmaker; Or, The sayings and Doings of Samuel Slick, of Slickville. This book, written by Thomas Chandler Haliburton in 1836, follows a Yankee clockmaker, Samuel Slick, and his adventures in Nova Scotia. There are two recorded uses in the book, the first in a memory titled “The Preacher that Wandered from his Text” and the second titled “The Blowin’ Time.” The first use recounts, “And with that he turned right around, and sat down to his map and never said another word, lookin’ as mad as a hatter the whole blessed time.” The second use adds, “Father, he larfed out like anything; I thought he never would stop; and sister Sall got right up and walked out of the room, as mad as a hatter. Says she, ‘Sam, I do believe you are a born fool, I vow.” None of the early recorded uses of the phrase either in England or in North America have any explanation surrounding them, showing the phrase had wide enough usage that readers readily understood the phrase.

The treatment of those afflicted by mercury poisoning, or “mad hatter disease” due to their jobs, was poor. In the United States it became known as the “Danbury shakes” due to the mass hat making operations in Danbury, Connecticut, and the symptoms that developed in the hatters there. In Europe, the hatters did not fare any better, and were treated as drunks by others in the community. These conditions were well known, and as early as 1860 it began to be mentioned in the medical community. However, through the 1880s and 1890s the Connecticut State Board of Health only monitored these conditions, deemed that it did not affect the general public, and consequently did nothing. It was not until 1913 that reforms started to occur. It was added first to the Workmen’s Compensation Act of 1913, then recognized as an occupational hazard in 1919. Mercury was finally banned in the production of hats in 1941, when the United States Public Health Service brokered an agreement between manufacturers and the unions.

What influence do you think a hat could have on the world? Do you think about fashion, celebrities, maybe the baseball hat or the knit cap hanging in your closet? You probably do not think about international relations, global trade, and economic competition that spurred global exploration, and started and averted wars, but the hat played a role in all these things.

Top hats were at first created from felt composed of combed and matted fibers from beaver fur. Although the top hat was not the first and certainly not the only driver of the fur trade, the pursuit of beaver pelts spurred much of the early European exploration of North America, as western traders sought out indigenous peoples with whom to trade for pelts. These trading relationships introduced European goods and new technologies, including metal objects such as firearms and tools, to native American cultures–but also encouraged further European expansion in the Americas that harmed those same native peoples. One argument postulates that English expansion westward from the colonies along the east coast as they sought more fur trade—and the French military response—sparked skirmishes that escalated into the French and Indian War. Debt from the war prompted Great Britain to impose many of the taxes that led to the American Revolution. A dispute over hat felt contributed to the founding of the United States.

Of course, hats had a local impact, too. If you were one of the hat sellers represented here, the top hat represented a major component of your livelihood and your ability to care for your own needs and those of your family. William A. Heitshu, a Civil War veteran, completed his military service in May 1863, and by December of 1865 he advertised clothing for men and women at a shop at 14 North Queen Street in Lancaster, using materials including beaver and silk. Heitshu’s hat and fur business did not prosper. A year later, in December 1866, he advertised the liquidation of his inventory, and in February and March 1867, he sold his furniture and other items, including showcases, a safe, and a sewing machine. Not to be defeated, though, by September 24, 1870, Heitshu was back in business on the south side of Queen Street, this time as a dealer of sewing machines.

Example of a 1860s top hat. Inside of the hat is the manufacturing marking of W.A. Heitshu of Lancaster, PA

Over in Reading, at 609 Penn Street, James C. Brown seems to have had a more successful foray into hat manufacturing, if not one completely free of troubles. Interviewed along with several other merchants and craftsmen by the Reading Times and Dispatch for an article published September 27, 1877, Brown spoke of the expenses faced by shops away from cities that could not place quick, small orders with nearby factories, and therefore had to invest in expensive inventories. Once, a customer tried to pay him with a forged check. On April 5, 1880, the same newspaper announced under “Recent Removals” that a competing hatter was moving onto Penn St, just a few blocks away—called “Brown Bros.” Imagine competing with another shop just a few doors over, with practically the same name!

Adam Rise was not only a hatter, but a fire marshal. The Lebanon Daily News wrote on December 18, 1872, in an article titled “A Fine Hat,” that he had “… [worn] one of the tastiest fire hats in the State, on our late firemen’s parade.” Fitting, then, that he went on to sell his own hats. From a shop at 829 Cumberland Street, he advertised not only retail, but wholesale pricing, too. Perhaps he could have supplied Brown in Reading!

The Lebanon Daily News on December 18, 1872 described Adam Rise’s fire hat as, “a black New York fire regulation hat, painted red below the rim. Eight cones run from the center down the crown, brought out in the gold-leaf. The shield is white, with “Perserverance” [the name of the fire company], and “Chief Marshal” on red background ; a fancy figure “1” occupies the centre in black relief, above which stands a white star on blue ; the initial background is also blue.” Design elements aside, it may have looked something like this hat.

Image credit: Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

Beaver fur became more expensive into the 1830s as the population of the animals dwindled due to trapping, and silk took over as a preferred material for making top hats. Most top hats in this collection are made of silk–which you can see in the sheen as the shiny material catches and reflects the light. The top hat’s material impact on trade and commerce carried over from the fur to the silk trade, where several international crises in the 1870s kept American diplomats busy as they tried to maintain the flow of Asian and European silk to American hatters and clothiers. It was not just about top hats–it was about trade, livelihood, and international diplomacy. Think about that the next time you don your favorite hat! Where was it made? How were the workers treated? In what conditions did they labor?

Bibliography

Accession Files & Tags: S2007-06-001, S2024-08-018, S-2024-08-088, S2024-08-092, S2024-08-093, S2024-08-094, S2024-08-095. Shippensburg Fashion Archives & Museum, Shippensburg, PA.

Bates, Samuel. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-6; Prepared in Compliance With Acts of the Legislature. Vol. IV. Harrisburg, 1870.

Carlos, Ann M. and Frank D. Lewis. Commerce by a Frozen Sea: Native Americans and the European Fur Trade. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010.

Cleveland Clinic. “Mercury Poisoning: Symptoms, Causes & Treatment.” https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/23420-mercury-poisoning.

Connecticut History | a CTHumanities Project – Stories about the people, traditions, innovations, and events that make up Connecticut’s rich history. “Ending the Danbury Shakes: A Story of Workers’ Rights and Corporate Responsibility – Connecticut History | a CTHumanities Project,” December 12, 2020. https://connecticuthistory.org/ending-the-danbury-shakes-a-story-of-workers-rights-and-corporate-responsibility/.

Ginsburg, Madeline. The Hat: Trends and Traditions. Barron’s Educational Series, 1990.

HathiTrust. “Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine v.25 (Jan-June 1829).” https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b5227750?urlappend=%3Bseq=9.

Haliburton, Thomas Chandler. “The Clockmaker; Or, the Sayings and Doings of Samuel Slick, of Slickville.” https://www.gutenberg.org/files/9196/9196.txt.

Henderson, Debbie. The Top Hat: An Illustrated History. Wild Goose Press, 2000.

“Lincoln’s Top Hat.” Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.si.edu/object/abraham-lincolns-top-hat:nmah_1199660.

Long, David. The Hats the Made Britain: A History of the Nation Through Its Headwear. Cheltenham, History Press, 2020.

Ma, Debin. “The Modern Silk Road: The Global Raw-Silk Market, 1850-1930.” Journal of Economic History, 56, no. 2 (June 1996): 330-355.

Martin, Horace T. Castorologia: Or the History and Traditions of the Canadian Beaver. Montreal, 1892.

McDowell, Colin. Hats: Status, Style and Glamour. Rizzoli, 1992.

Millward, Robert. “How Could a Beaver Start a War?” The History Teacher, 43, no. 2 (February 2010): 275-282.

“Newspapers,” Accessed September 3, 2024. https://www.newspapers.com. Provided access to the Reading Times & Dispatch, Reading Times, York Daily, York Gazette, York Democratic Press, York Dispatch, York Evening Dispatch, York Dispatch & Record, Lancaster Daily Evening Express, Lancaster Examiner & Herald, Lancaster Intelligencer, Pottsville Daily Republican, and Lebanon Daily News.

Peacock, John. Men’s Fashion: The Complete Sourcebook. Thames and Hudson, 1996

Perez-Garcia, Manuel. “Beyond the Silk Road: Manila Galleons, trade networks, global goods, and the integration of Atlantic and Pacific markets (1680–1840).” Atlantic Studies: Global Currents, 19, no. 3 (2021): 373-383.

“Pennsylvania Engine Co. No. 12 Fire Hat.” Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Accessed September 22, 2024. https://www.si.edu/object/pennsylvania-engine-co-no-12-fire-hat:nmah_1318726.

“Pennsylvania Hose Company Fire Hat.” Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.si.edu/object/pennsylvania-hose-company-fire-hat:nmah_1318704.

Picken, Mary Brooks. The Fashion Dictionary: Fabric, Sewing and Apparel as expressed in the Language of Fashion. Funk & Wagnalls, 1973.

Smith, Malcolm. Hats: A Very Unnatural History. Michigan State University Press, 2020.

Stevens, Scott Manning. “Tomahawk: Materiality and Depictions of the Haudenosaunee.” Early American Literature, 53, no. 2 (2018): 475-511.

Tenniel, John. “The Mad Hatter, Illustration by John Tenniel,” 1865. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed October 6, 2024. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MadlHatterByTenniel.svg.

Weaver, Paige. “Reconstructing A Nation Through Silk and Diplomacy: American Material Culture and Foreign Relations During the Reconstruction Era.” Journal of American Culture 43, no. 3 (September 2020): 232-253.

With special thanks to Shippensburg Fashion Archives & Museum Director Dr. Karin Bohleke and Graduate Assistant Dominic Curcio for providing access to the FA&M collection and records, providing interpretive guidance, and suggesting starting points for additional research.