SHIPPENSBURG’S STEWART FAMILY

The Stewart Family, who settled in South Central Pennsylvania between what is now Franklin and Cumberland Counties, in the 1770s, became one of the most notable contributing families in Shippensburg’s history. The family’s importance to the Shippensburg area revolves mostly around their importance as doctors. Dr. Alexander Stewart, the earliest known Alexander as there were many over the years, was one of the earliest doctors or medical practitioners in and around the Shippensburg area. He and his descendants would continue the “family tradition” of being doctors well up into the present; as the most recent, Dr. Alexander Stewart (b.1891), passed away in 1985. The Stewarts not only served the community as doctors, but also helped to expand the town economically into what it is today. One example would be Alexander Stewart’s granary, son of Dr. Alexander Stewart and Elizabeth (Hamill) Stewart, which provided a large economic boost to the area, especially since Shippensburg was a stop for the major railroads at the time. Over the years, the Stewarts would own many important buildings in Shippensburg. For instance, what is now the Shippensburg History Center is the original home of the Stewart Family when they moved to Shippensburg in the 1770s. The Jeffrey W. & Jo Anne R. Coy Public Library as well as 110 E King Street served as family residences for the Stewarts throughout the 1800s and even into the 20th Century.

A partial genealogy of Dr. Alexander Stewart (1891-1985)

Let us now examine the history and impact of four important fibers — cotton, linen, wool, and silk — through the lens of the clothing worn by members of the Stewart family.

KING COTTON

In the early 1800s, cotton became central to the American economy, especially in the South. Eli Whitney’s 1793 invention of the cotton gin revolutionized production, allowing cotton to overtake tobacco as the dominant crop by the 1830s. Fueled by European demand, particularly from Britain, the South grew increasingly reliant on cotton exports, leading to plantation expansion and entrenchment of slavery. By the mid-1800s, cotton accounted for over half of the United States gross domestic product, shaping both Southern and Northern economies. Northern merchants, especially in New York, profited from its trade, while the South remained agrarian and reliant on enslaved labor, contributing to sectional tensions that led to the Civil War.

Late 19th Century ladies’ cotton “Bosom Enhancer”

Cotton also transformed women’s fashion in the mid-19th century, becoming the most widely used fiber for clothing. Previously, linen and wool dominated, but industrial textile mills made cotton fabrics like muslin, calico, and gingham more affordable and accessible. Lightweight and practical, cotton suited middle-class women’s needs, as seen in this”bosom enhancer” worn by either Elizabeth Hamill or Eunice Wilson, wives of Dr. Alexander Stewart. This late 19th-century undergarment, a precursor to the modern brassiere, reflects a shift away from corsets toward more comfortable alternatives like bust improvers and bust supporters, paralleling the rise of more functional and less confining undergarments.

The mechanization of textile production made cotton accessible to all social classes, democratizing fashion. Cotton’s affordability and versatility also contributed to fashion’s evolution, with printed and dyed fabrics offering variety in everyday dress. While silk remained the choice for luxury, cotton became the preferred fabric for daywear and informal occasions.

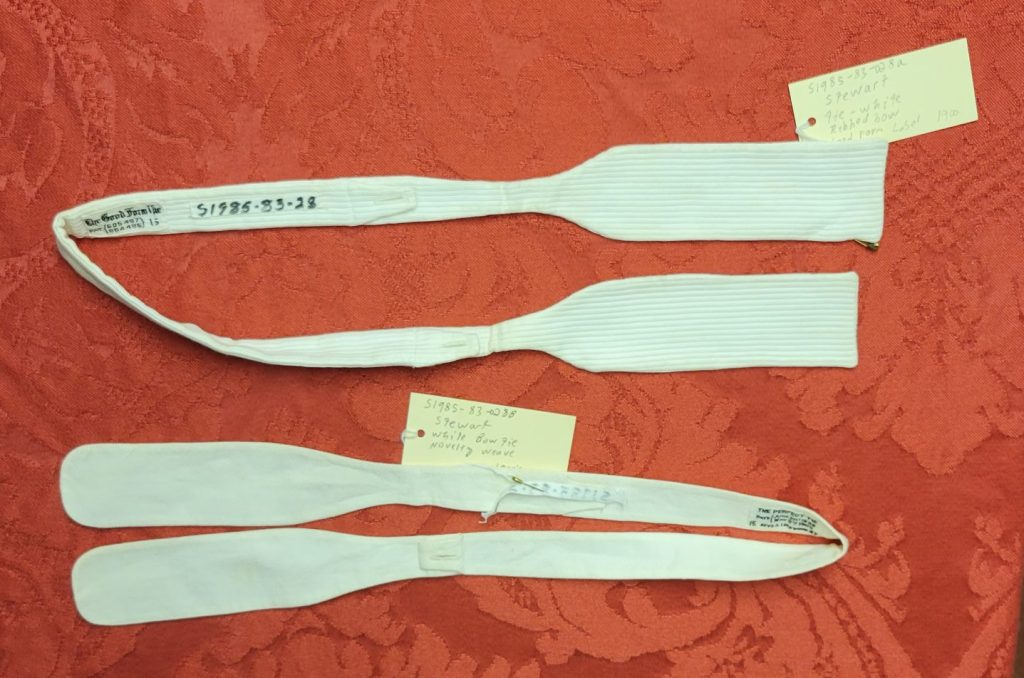

In the 1920s and 1930s, fashion trended toward practicality, reflected in Dr. Stewart’s choice of two white cotton bow ties over the more expected silk. Cotton’s durability made it a practical option for repeated use in formal settings, such as medical or social events. High-quality cotton ties, possibly made from luxury Pima or Egyptian cotton, were easier to care for than silk, appealing to a busy physician like Dr. Stewart. The bow ties, likely chosen for comfort and convenience, also suggest a balance between elegance and practicality, showing that even wealthy individuals could prioritize utility in their wardrobe choices.

White cotton bow ties worn by Dr. Alexander Stewart ca.1920.

LINEN

Though both natural fibers, cotton and linen differ in cultivation, harvesting, and processing. Cotton, from the cotton plant (Gossypium), grows best in warm climates and is processed through ginning to separate seeds from fibers, which are then spun into yarn. Cotton fibers are short, soft, and flexible, making them easy to spin, though they wrinkle easily. Cotton is preferred for soft, comfortable clothing like shirts and undergarments, while linen is chosen for its strength and breathability, ideal for more structured garments like summer suits and high-end shirts. Linen’s longer production process makes it more expensive, but its durability and moisture-wicking properties make it highly valued.

A lady’s 19th-century linen bodice (undergarment) worn by Ella Jane Stewart, Dr. Alexander Stewart’s mother.

By the early 20th century, Pima and Egyptian cottons were recognized for their superior qualities. Both have longer fibers that produce softer, stronger fabrics, like Dr. Stewart’s white cotton bowties, demonstrating how high-quality cotton could be incorporated into formalwear. These luxury cottons offered comfort, durability, and elegance, accessible to the wealthy and upper-middle classes, though still more affordable than silk.

Linen, derived from flax (Linum usitatissimum), grows in cooler climates. Flax fibers, longer than cotton, require a more complex spinning process but produce a strong, smooth thread. Linen is crisp and durable, though less flexible than cotton and more prone to wrinkling. The labor-intensive process of retting, scutching, and hackling makes linen production more time-consuming. Philippe de Girard’s 1810 flax spinning frame sped up production, though linen still remained more costly than cotton.

Historically, linen was used for fishing nets, sails, as well as clothing. In colonial America, women wove linen from locally grown flax as a form of resistance to the slow and inefficient British mercantilism. However, with the rise of the cotton gin and the abundance of cotton, the American linen industry declined. In Europe, particularly Scotland, linen remained prominent, but after World War I, shortages of flax and the rise of artificial fibers like nylon and rayon led to its decline.

Despite its waning popularity, linen still played a role in women’s fashion. Ella Jane Stewart, mother of Dr. Alexander Stewart, likely wore this beige linen bodice adorned with scalloped cuff sleeves, embroidery, and pearl buttons. Linen was often used in needlework practice, so the intricate detailing may have been painstakingly hand-sewn. This bodice, with its close-fitting bust and flared sleeves, reflected the fashion and refinement of a well-to-do household that valued linen’s durability and elegance despite its higher cost.

WOOL AND WAR

A checkered woolen “flat cap” worn by Dr. Alexander Stewart in the 1920s. The flat cap was, in this era, staple headwear for gentlemen of every social stratum.

Leading up to World War I, wool played a crucial role in the economies of Europe and the U.S., valued for its warmth, durability, and versatility. It was used for everyday clothing and luxury items, with demand surging as the war began, especially for military uniforms and supplies. Wool production increased, prices rose, and global supply chains were strained as key wool-producing countries like Australia and New Zealand were embroiled in the conflict. Innovations emerged, including substitutes like cotton blends and synthetic fibers. While the wool industry was vital to the war effort, it faced post-war challenges from changing fashion and competition from other fabrics.

Before World War I, the wool industry thrived, particularly in Great Britain, France, Germany, and the U.S. The truly global nature of the Great War disrupted markets, but wool remained essential, driving countries to adapt to sustain production. This British woolen flat cap owned by Dr. Alexander Stewart exemplifies wool’s economic significance during and after the war. Popular in the 1920s, this flat cap, once associated with the working class, became fashionable among middle- and upper-class men, symbolizing social mobility and cross-class appeal.

Great Britain was a dominant force in wool production, responsible for 90% of the world’s supply before the war. Post-war, Britain struggled to regain pre-war levels but continued to lead the industry, benefiting from a robust domestic market and avoiding European competition. Britain’s wool industry provided economic stability and opportunities for workers, maintaining its global standing despite setbacks.

The 1920s saw dramatic cultural shifts following the devastation of World War I. The “Roaring Twenties” brought social rebellion, modernization, and the liberalization of fashion, music, and gender roles. Men’s fashion embraced a more youthful, less formal style, with checkered wool hats like Dr. Stewart’s flat cap symbolizing modernity. These caps reflected the era’s move toward self-expression and casual elegance, while the rise of Jazz music, led by artists like Louis Armstrong, provided the era’s iconic soundtrack. Dr. Stewart’s flat cap, modest compared to the flashy suits and dresses of the time, remains a significant emblem of the period’s evolving style.

TAFETTA: “TWISTED WOVEN” LUXURY

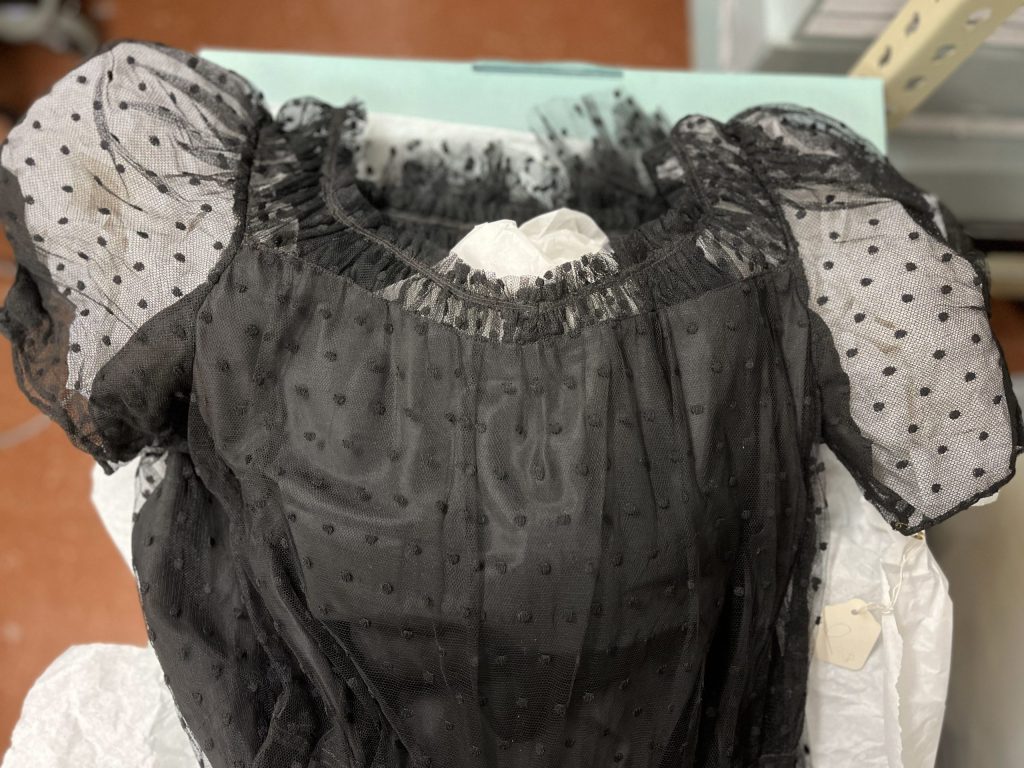

Upper portion of a 1940s-era black silk taffeta party dress worn by Dorothea Stewart, Dr. Alexander Stewart’s wife

Taffeta fabric has been a mainstay in fashion since its origins in 12th-century Attabiya, Baghdad, eventually spreading through Persia and into Europe before reaching North America by the early 20th century. The name “taffeta” derives from the Persian word taftah, meaning “twisted woven.” Traditionally made from silk, taffeta became prized for its sheen and slightly stiff texture, making it ideal for formal wear such as ball gowns, evening dresses, and garment linings. By the 19th century, taffeta symbolized luxury and elegance in Europe and the United States, its distinct rustling sound, or “scroop,” adding to its appeal. This sound would have been a notable part of a young lady’s first formal experience, perhaps as a bridesmaid or at a dance, wearing an elegant taffeta gown that “scrooped” as she moved.

Over time, synthetic fibers like rayon and made taffeta more accessible, though it retained its air of sophistication. By the 1950s, Italy, France, and Japan had become leading producers of taffeta, with the fabric remaining a symbol of wealth and social status. Before synthetic fibers were widely used, silk taffeta was prohibitively expensive, accessible only to the wealthy. The process of producing silk—from cultivating silkworms to weaving the delicate fibers—meant that owning a taffeta gown often required a significant financial sacrifice for middle- and lower-class families. However, with the introduction of synthetic fibers, taffeta became more affordable, allowing more modest families to consider it for special occasions like weddings and proms.

Lower portion of Dorothea Stewart’s silk taffeta party dress from the 1940s.

Despite its increased accessibility, taffeta continued to be favored by royalty and the elite for its ability to create structured silhouettes in ball gowns and formal wear. It was also used in corseting and men’s jackets. Even today, taffeta remains one of the most luxurious fabrics available, versatile in its texture, sheen, and prints. Though it was traditionally made from silk, modern taffeta often includes a blend of fibers intricately woven in patterns that catch the light, giving the material its signature shine. Taffeta can be dyed or printed in various ways, including piece-dyed, yarn-dyed, or moiré finishes.

The Stewart family of Shippensburg demonstrated their prominent social status through their fashion choices, such as a 1940s black taffeta evening gown worn by Dr. Alexander Stewart’s wife, Dorothea. Her dress reflects the everyday use of taffeta in 20th-century party wear. As the wife of a respected physician in mid-20th century America, Dorothea needed to maintain an elegant fashion sense for public events. The dress’s design, with its overlaying netting and dotted Swiss pattern, highlights both the versatility of taffeta and the importance of fashion in her social circles.

During the 1930s and 1940s, as World War II escalated, taffeta shifted from being a fashion fabric to serving practical purposes, particularly in the production of parachutes. A strong weave of taffeta was used for parachutes essential to airborne assault troops and pilots. Early in the war, silk, much of it sourced from Japan, was the primary material used for parachutes. However, as Japan entered the war and silk supplies dwindled, silk parachutes became scarce, and taffeta became a substitute. The production of parachutes during the war was massive, and silk became a rationed commodity alongside other war essentials like leather, sugar, and steel. This transformation of taffeta—from a symbol of elite luxury to a lifesaving material for soldiers—illustrates how quickly a fabric’s perceived value can change in times of crisis.

After World War II, discarded silk parachutes were repurposed creatively due to shortages and the luxury of silk. Brides often made wedding gowns from parachute fabric, symbolizing resilience and love in difficult times. Silk parachutes were also used for blouses, lingerie, children’s clothing, and household items. In some areas, parachutes dropped during the war were collected and repurposed for scarves, bags, or to repair damaged clothing, reflecting the material’s value and the resourcefulness of people during wartime.

Taffeta experienced a resurgence in the 1950s with the popularity of the “New Look,” as its structured silhouette became fashionable again. Dorothea Stewart’s evening gown from this period, featuring gatherings at the neckline and hips to accentuate the figure, is a perfect example of taffeta’s lasting appeal and versatility in both fashion and function.

SUMMARY

In the early 19th century, cotton became the juggernaut in the American economy, particularly in the South. Technological advancements like Whitney’s cotton gin allowed cotton to surpass tobacco as the dominant crop, further entrenching the reliance on slavery and fueling sectional tensions that eventually led to the Civil War. Cotton also transformed women’s fashion, becoming the most widely used fiber by the mid-19th century, making textiles like muslin and calico affordable for the lower and middle classes. Innovations in cotton production, such as high-quality Pima and Egyptian cotton, enhanced its use in formalwear, exemplified by Dr. Alexander Stewart’s white cotton bow ties. While cotton was democratizing fashion, other fibers like linen and wool continued to play significant roles, with linen being favored for its strength and luxury, and wool being essential to economies and the military during World War I. Meanwhile, taffeta, initially a symbol of wealth, became more accessible with the rise of synthetic fibers. However, during World War II, taffeta was repurposed for parachutes, showcasing how its utility expanded beyond fashion. The enduring appeal of fabrics like taffeta in mid-20th-century formalwear, such as Dorothea Stewart’s evening gowns, highlights the evolving roles of textiles in both everyday and luxury contexts.

____________________________

REFERENCES

Baptist, Edward E. The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. Basic Books, 2014.

Barnett, Vivien. “Spinning the Fabric of a Nation: A Nineteenth-Century Spinning Wheel and Early Linen Production in Maryland.” Maryland Center for History and Culture. 2020. Spinning the Fabric of a Nation: A Nineteenth-Century Spinning Wheel and Early Linen Production in Maryland – Maryland Center for History and Culture (mdhistory.org).

Beckert, Sven. Empire of Cotton: A Global History. Vintage, 2015.

Cole, Daniel James and Nancy Diehl. The History of Modern Fashion. 2015. The History of Modern Fashion: From 1850 (2015) | Fashion History Timeline (fitnyc.edu).

Crowston, Clare Haru. Fabricating Women: The Seamstresses of Old Regime France, 1675–1791. Duke University Press, 2001.

Franklin, Harper. “1870-1879.” in Fashion History Timeline. 2019. 1870-1879 | Fashion History Timeline (fitnyc.edu).

Jenkins, David. The Cambridge History of Western Textiles. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Kaity. “What is Taffeta? The Origins, Benefits, and How It’s Made.” Contrado, 2020.

Lehman, LaLonnie. Fashion in the Time of the Great Gatsby. Shire Publications: 2013.

“Line History and its Significance.” Ecosit, 2024. Explore the History, Facts, and Downfall of Linen – ECOIST.

Riello, Giorgio. Cotton: The Fabric that Made the Modern World. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Rohan. “Taffeta in Historical Fashion.” Knowing Fabric, 2024.

Stephens, S. G. “The Origins of Sea Island Cotton.” Agricultural History. 50 (2): 393.

Wong, Melanie. “1870.” in Fashion History Timeline. 2019. 1870 | Fashion History Timeline (fitnyc.edu).